Why Spring Gets About 30 Seconds Shorter Every Year

Spring arrives on Friday, and you might want to make the most of it. The season of flowers and showers actually gets shorter every year by about 30 seconds to a minute, due to astronomical quirks, researchers say.

This year, spring officially starts at 6:45 p.m. EDT on March 20, according to the U.S. National Weather Service (NSW). At that exact moment, which is called the vernal equinox, the Earth's axis will reach a halfway mark, where it points neither toward the sun (as it does on the summer solstice) nor away from the sun (as it does on the winter solstice), said Gavin Schmidt, the director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City.

But for thousands of years, spring has been losing time in the Northern Hemisphere. This year, summer is the longest season, with 93.65 days, followed by spring with 92.76 days, autumn with 89.84 days and winter with 88.99 days, said Larry Gerstman, an amateur astronomer in New York. (Gerstman got his values from "The Astronomical Tables for the Sun, Moon and Planets," second edition, written by Jean Meeus and published in 1995 by Willmann-Bell, Inc.)

As the years go on, spring will lose time to summer, and winter will lose time to autumn. In the year 3000, the seasonal lengths will have shifted in the Northern Hemisphere: summer will be 93.92 days, while spring will be 91.97 days, autumn 90.61 days and winter 88.74 days, Gerstman said. [6 Signs Spring Has Sprung]

But why is this happening?

The Earth's seasons are caused by the tilt of the Earth on its axis (not by how close the planet is to the sun). This tilt of 23.5-degrees from the straight-up-and-down position means that for six months of the year, the Earth's Northern Hemisphere is leaning slightly toward the sun, whereas during the other six months, the Southern Hemisphere leans toward the sun.

The main reason spring is getting shorter is that the Earth's axis itself moves, much like a wobbling top, in a type of motion called precession.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spring ends at the summer solstice, and because of precession, the point along the Earth's orbit where the planet reaches the summer solstice shifts slightly. Next year, the planet will reach the point in its orbit of the solstice slightly earlier.

Spring will end, and summer will begin, just a little bit earlier in the year. [50 Interesting Facts About The Earth]

Over thousands of years, the shift in the time of the vernal equinox becomes more apparent. For instance, spring will be shortest in about the year 8680, measuring about 88.5 days, or about four days shorter than this year's spring, Gerstman said. (After that point, spring will lengthen again.)

Why spring is shorter than summer

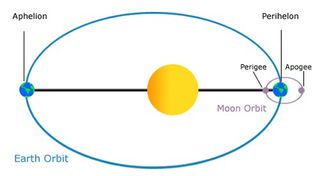

Other aspects of Earth's movements also affect the exact length of the seasons. One is that Earth's orbit around the sun is not a perfect circle, but instead is elliptical. This means that the planet is not always the same distance from the sun. These days, Earth reaches the point in its orbit where it is closest to the sun, an event called perihelion, in early January. (In Greek, peri means near, and helios signifies the sun.)

At the point of perihelion, the Earth is about 91.6 million miles (148 million kilometers) away from the sun. When the Earth is farthest from the sun — in early July, during aphelion — the distance is about 94.8 million miles (153 million km).

This change in distance from the sun, of about 3.2 million miles (5 million km), isn't much compared to Earth's total distance from the sun, according to NASA, and people don't notice it. But the difference is large enough to change the speed of the Earth as it travels in its orbit. The Earth moves fastest when it's closest to the sun, and slowest when it's farthest, Schmidt said.

"We go through winter quite quickly, whereas in the summertime we're far away from the sun, and so we're going to go slower,"Schmidt told Live Science.

This change in speeds affects the length of the seasons. The Earth moves the fastest along its orbit path between December and March, hence both winter and spring are shorter than summer and autumn, he said.

In the year 1246, Earth reached perihelion on the day of December solstice, said Joe Rao, a New York based meteorologist and astronomer (Rao is also a contributing writer at Live Science.) This year, Earth reached perihelion on Jan. 4.

"Near the year 3000, perihelion will take place near Jan. 20, and near the year 4000, it will take place near Feb. 7, and so on," Rao told Live Science in an email.

At these distant dates, the Earth will be moving at its fastest speed later during the year, making spring even shorter. Perihelion will occur on the March equinox in the year 6430.

But spring will be shortest when perihelion occurs halfway through the season. And eventually, as perihelion and precession continue to change Earth's speed and wobble, spring will lengthen again, Schmidt said.

However, these changes are so minute that most people won't notice a difference during their lifetimes, Schmidt said. In fact, since most people associate spring with warm weather, he said, they will be more likely to notice that warm weather is beginning earlier in the year, because of climate change, than to be aware of the changing orbit.

"It's not something that anyone is going to notice unless you're an astronomer or a paleoclimatologist," Schmidt said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.