Desert Blooms: Spectacular Photos of Organ Pipe Cactuses

The organ pipe cactus (Stenocereus thurberi) is one of the more spectacular species of cactus found in the Sonoran Desert. It is only found naturally in the northern region of Sinaloa, the western region of Chihuahua, throughout Sonora and in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Check out these fascinating photos of the organ pipe cactus.

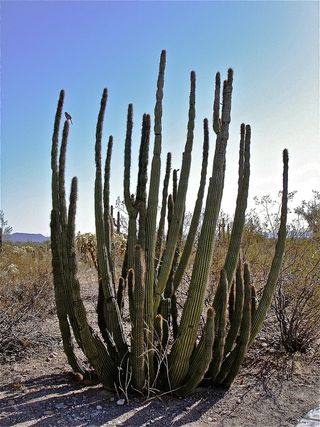

A spectacular species

Within the continental United States, the organ pipe cactus is only found in the extreme south-central part of Arizona. The cactus grows at elevations ranging from sea level to 3,000 feet (910 meters). (Credit: NPS)

Sensitive at heart

Since the organ pipe cactus is very sensitive to frost, they tend to grow on the southern-facing mountain slopes found within this region of the Sonoran Desert. Unlike the more common saguaro cactus (Cereus giganteus), the organ pipe cactus can stand temperatures no lower than 25 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 4 degrees Celsius) for only a very short period of time. This heat-loving cactus gets its name from the many slender stems that are said to resemble an old-fashioned, resonating pipe organ. (Credit: NPS)

A strong foundation

The columnlike stems of the organ pipe cactus grow from a base just above ground level. These water-storing stems can grow to a height of more than 25 feet (7.6 m) and the largest stems will have between 12 to 17 dark-green ribs with a diameter of about 6 inches (15 centimeters). When a stem branches out, most likely that stem has been damaged by frost or the tip of the stem has been broken off. It takes about 35 years for an organ pipe cactus to reach maturity, and mature plants may be 12 feet to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) wide. Stems tend to grow about 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) longer each year. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient of days

On the crest of the ribs are found a continuous series of regularly spaced areoles, the highly reduced branches of cacti and a key identifying feature of all species of cactus. From the organ pipe areoles grow nine to 10 brown spines that can measure up to 2 inches (5 cm) long. An organ pipe cactus can live for more than 150 years and as they age, the spines turn gray. The stems of the organ pipe cactus grow continuously from their tips and a slight constriction line that encircles the stem marks each season of growth. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Nature's ornaments

Once an organ pipe cactus reaches maturity it begins to produce beautiful white flowers tipped with shades of purple or pink. The blooming season is typically during the months of late April, May and June. The cactus produces funnel-shaped flowers that measure about 3 inches (8 cm) across. Like all night-blooming cereus cacti found in the Sonoran Desert, the blooms of the organ pipe cactus only remain open for one night before closing by mid-morning the following day. (Credit: NPS)

Friend of the cactus

The primary pollinator for these attractive flowers is the lesser long-nosed bats, Leptonycteris yerbabuenae. Lesser long-nosed bats are an endangered species that migrate each spring into the organ pipe cactus region to feast on cacti pollen, nectar and fruit. The lesser long-nosed bat shown here is covered in yellow cactus pollen. (Credit: NPS)

Desert fruits

About a month after pollination, large, spiny, tennis ball-sized fruit begins to ripen on the many stems of the cactus. When ripe, the fruit will lose its spines and split open revealing a red, fleshy pulp encompassing hundreds of small, glossy black seeds. The fruit is edible and has long been harvested by the indigenous people of the Sonoran Desert. The fruit can be eaten raw, dried for later consumption, turned into a type of jelly and even fermented to make an alcoholic drink. Locals have long referred to the organ pipe cactus as "pitaya dulce," which is Spanish for "sweet pitaya." (Credit: NPS)

An extreme life

Like all of the native plants found in the arid Sonoran Desert, the organ pipe cactus survives by adapting to extreme sunshine and long periods of infrequent rain. They are unique in that they seem to grow well on unprotected hillsides, without the shading advantage of a "nurse plant." To survive long periods of time without rain, the organ pipe cactus' waterproof skin helps slow any evaporation of the water stored in the fleshy pulp of the plant's stems. The thousands of sharp spines also provide small areas of shading on the skin of the stems, helping to slow evaporation. (Credit: NPS)

A national monument

In south-central Arizona, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) site shares an area of land designated as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. This 520 square-mile (1,350 square kilometers) reserve and national monument shares the international border with the Mexican state of Sonora, and helps to preserve a large stand of organ pipe cactuses. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

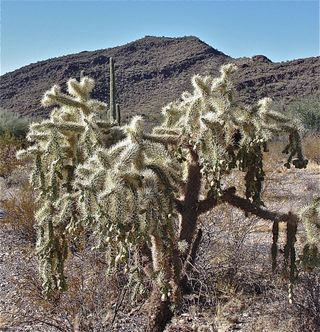

A plethora of plants

Even though this biosphere reserve landscape is located in one of the most hostile, arid environments in North America, more than 26 species of cactus can be found within its boundaries. Shown here is a chain fruit cholla (Opuntia fulgida) that seems to be growing well in the heat, drought and intense sunlight found in this natural environment. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

A safe haven

One of the most surprising and unique features of this UNESCO site is Quitobaquito Oasis. This shallow, freshwater pond is only 200 yards (183 m) north of the international border and is created by a fault in a nearby granite-gneiss hillside. It is one of very few reliable water sources found anywhere in the Sonoran Desert, and is home to the endangered Quitobaquito pupfish (Cyprinodon eremus) and the Sonoran Mud Turtle (Kinosternon sonoriense). (Credit: NPS)

Natural grandeur

The ancestors of the organ pipe cactus can be found today across all the regions of the Sonoran Desert, but once grew in the warm, dry tropics closer to the equator. At the end of the last Ice Age, some 12,000 years ago, this species of cactus began a slow migration north. Botanists estimate that the species arrived in its current Sonoran Desert home about 3,500 years ago. Today, they add their natural grandeur to one of the most spectacular landscapes found anywhere in North America. (Credit: NPS)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Most Popular