Antarctica's Mysterious Mountains Preserved By Ice

Earth's best-kept secret to looking young is buried under Antarctica's deep, old ice.

The planet's fountain of youth is frozen water mantling Antarctica's mighty Gamburtsev Mountains, a new study reports. Roughly the size of the European Alps, by all rights, the 100-million-year-old Gamburtsevs should resemble the rolling Appalachians by now, having eroded away beneath grinding ice. Instead, the Gamburtsevs are as rugged as the Rocky Mountains.

"The question is, why does it look young?" said lead study author Timothy Creyts, a glaciologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "We think that erosion stopped for the Gamburtsevs and most of East Antarctica once the ice sheet started getting large enough." [50 Amazing Facts About Antarctica]

No one has ever laid eyes on the Gamburtsev Mountains. The deep valleys and steep ridges are completely entombed by ice that is up to 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) thick. The mountains are hidden near the 70 degrees East longitude line beneath Dome A (or Argus Dome), one of the coldest places on Earth.

But if Antarctica melted, the Gamburtsevs' peaks and ridges would be one of the continent's highest mountain ranges. The mountaintops now measure more than 8,850 feet (2,700 m) above sea level and would bounce back to more than 10,800 feet (3,300 m) with the ice sheet missing.

"It's a massive mountain range, and it's very fresh-looking," Creyts said.

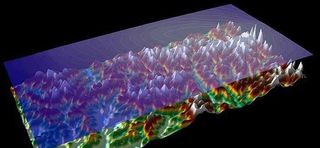

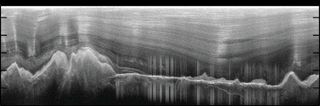

To see through the ice, an international group of scientists flew ice-penetrating radar instruments across the Gamburtsev Mountains over a four-week period in December 2008 and January 2009.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The survey data revealed a network of subglacial streams and lakes flowing through deep, long valleys within the mountains. This is the source of the frozen mantle that protects the Gamburtsevs from erosion, the researchers reported Nov. 17 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

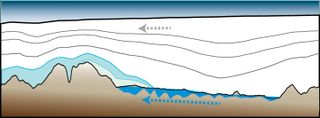

Where the Gamburtsevs' valleys and ridges are aligned against the direction of ice flow, the water is forced uphill. Water flows against gravity's pull in Antarctica because of the pressure from the overlying ice. But at the higher elevation of the ridges, where temperatures are colder, the radar survey showed that water freezes. This is mainly because the ice sheet is thinner and cold surface temperatures can penetrate downward. The thin coating of frozen water ice is enough to shield the rocks from wear and tear.

Though humans may sandblast their skin to look younger than their years, removing layers of rock with erosion quickly ages a mountain range. But without liquid water between ice and bedrock, glaciers erode very slowly. (Glaciers can still flow without slippery water as lubricant, but most of the movement is internal, through folding and warping of the ice.)

"Wherever we see freezing in the radar data, areas of erosion were really reduced," Creyts told Live Science.

The researchers have identified landscape features in Canada and northern Europe that may have formed by similar processes during past ice ages, Creyts said. Two examples are the Torngat Mountains in eastern Canada and the Scandinavian Mountains that run down the Scandinavian Peninsula. Both are old mountain ranges that were buried under ice sheets. "We think there is a land surface record of the processes we see in the radar data," Creyts said.

The deep, long valleys, cirques and jagged, narrow ridges revealed in the survey data are evidence that the Gamburtsev Mountains were chiseled by glaciers at some point, but the researchers think these features were carved starting 45 million years ago, as the planet gradually moved toward a colder climate. The vast Antarctica ice sheet was in place as early as 34 million years ago.

Since that time, Antarctica's ice has advanced and shrunk as Earth swung through warmer and colder periods, but the researchers think "cold-based" glaciers similar to today's ice sheet also protected the Gamburtsev Mountains from erosion. The Gamburtsevs' high elevations are thought to be an important ice reservoir for Antarctica, sheltering mountain glaciers even during hothouse climates.

"The Gamburtsevs have remained cold since the initial start of the ice sheet," Creyts said.

Editor's note: This story was updated Nov. 21 to correct that the Gamburtsevs would not be the highest spot in Antarctica if the ice sheet melts.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular