Drug Could Regrow Hair in Some with Hair Loss

Most hair-loss drugs currently available may stop hair loss, but don't cause hair to regrow. Now, new research suggests that a drug already used to treat people with other conditions could restore hair growth in patients with one disease that can cause hair loss.

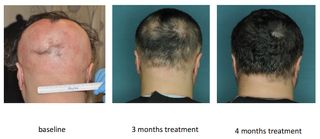

In a small new study, three people who took a drug called ruxolitinib daily for four to five months saw a complete regrowth of their hair. The patients had a condition called alopecia areata, which is an autoimmune disease that causes the loss of hair from the scalp or other areas of the body.

The drug used in the study is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat people with myelofibrosis, a serious bone marrow disorder.

In the new study, the investigators also determined the cellular mechanism that causes hair loss in people with alopecia areata, which was not completely understood before.

"Additional clinical trials are needed to test the effectiveness of this drug in more patients in larger studies," said study author Angela M. Christiano, a professor of dermatology and genetics at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. "However, for patients with alopecia areata, this is an exciting result, because it offers a potential new class of drugs that have not been tried before in this disease, with some promising early results." [4 Common Skin Woes, and How to Fix Them]

There is currently no approved treatment that can restore hair in patients with alopecia areata, which usually starts with the loss of small patches of hair on the scalp. In some cases, the condition can lead to the loss of all hair on the scalp or body.

Alopecia areata affects about 2 percent of the population, and about 6.5 million people in the United States have it, according to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The course of the disease is highly unpredictable —patients' hair may grow back and fall out again at any point — and differs from one patient to another. People with alopecia often suffer psychologically and emotionally.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers already knew that hair loss in people with alopecia occurs when cells of the immune system attack the base of the hair follicles. But until now, it was not clear which type of cell was responsible for this attack.

In the new study, the investigators found that a certain set of T cells are responsible for attacking hair follicles, and they also determined how those cells receive instructions to attack hair follicles. The investigators identified key immune pathways that could be targeted by drugs called JAK inhibitors.

Prior to the testing the drug on people with alopecia, the researchers tested two FDA-approved JAK inhibitors — ruxolitinib and tofacitinib— on mice with extensive hair loss from the disease, and found that the drugs effectively stopped the attack of T cells on hair follicles. Within 12 weeks of treatment, the drugs completely restored the mice's hair, and the hair remained for several months after stopping the treatment.

When the researchers tested ruxolitinib in the three people with the disease, they found that the attacking T cells disappeared from their scalps, and the patients regrew their hair.

"We believe this is a very exciting step forward for the treatment of alopecia areata," Christiano told Live Science. "We hope these findings will inspire future efforts to pursue the development of JAK inhibitors for this disease and represent a first rationally-selected treatment based on some exciting new scientific findings."

The researchers have not so far observed any adverse effects of ruxolitinib in their small trial, Christiano said.

"In patients who do not have chronic illnesses and are otherwise healthy, the likelihood of side effects [from taking ruxolitinib] is smaller than in patients who have chronic illnesses," she said. "Side effects can include infection, and changes in certain blood tests such as a drop in platelets or anemia."

The new study was published online today (Aug. 17) in the journal Nature Medicine.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.