$2 Million Competition Aims to Monitor Ocean Health

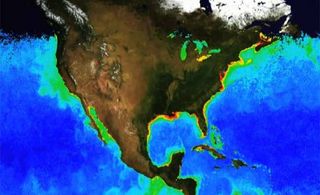

The planet's oceans are gradually becoming more acidic, in turn threatening the life and ecosystems that call the seas home. Yet the technology for measuring ocean acidification is inadequate or expensive, scientists say.

To tackle the problem, the X Prize organization is offering two $1 million prizes in a competition to develop accurate and affordable sensors to measure ocean acidity, or pH, that can help provide a clearer picture of the effects of ocean acidification.

"Because of the underinvestment in ocean science and research, there aren't enough tools present to measure what's happening in the sea," said Paul Bunje, the lead scientist behind the ocean health prize. "We've mapped the dark side of the moon and Mars to higher resolution than the bottom of the ocean." [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

A better sensor

Humans continue to pump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and at least a quarter of that amount gets absorbed by the oceans, researchers say. There, it changes the ocean's chemistry, making it more acidic.

"A good number of ocean scientists say ocean acidification is the biggest threat to ocean health," Bunje told Live Science.

Ocean acidification has reached unprecedented levels, which could affect the health of sea life, such as corals, and harm fisheries and tourism that depend on thriving marine ecosystems, researchers say.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Wendy Schmidt Ocean Health X Prize, launched in September 2013, will award two $1 million prizes to teams that develop either the most accurate or the most affordable ocean pH sensors. Anyone can compete, and teams or individuals can register for the competition until June 30.

After that, the competition will proceed in three phases: In September, teams will have three months to test their devices in a lab; in February 2015, the teams will take part in trials at the Seattle Aquarium; and in spring 2015, finalists will test their devices off the coast of Hawaii, at depths of more than 9,800 feet (3000 meters) — 50 percent deeper than any pH sensor has ever been tested.

So far, 70 teams from 19 countries have signed up to participate. The competitors include academics, large and small companies, "garage innovators" and high school clubs, Bunje said.

No easy solutions

Current sensors for measuring ocean acidity can't operate in all parts of the ocean, such as extreme depths, and are also incredibly expensive, representatives from the X Prize organization said.

The chemistry involved in measuring acidity can be challenging, especially in seawater, Bunje said. For example, litmus paper tests — a standard lab technique for measuring pH — use a dye that reacts with water and changes color depending on the acidity, but the very act of measuring pH changes the pH.

The pH of a water sample also changes with temperature and pressure, as well as when it's in the presence of sea life, Bunje said. If teams can design ways to measure pH well, they could solve many other ocean problems, he said.

The prize comes on the heels of another successful X Prize: The Wendy Schmidt Oil Cleanup X Challenge, prompted by the 2010 BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, was a $1.4 million competition to develop better technology for cleaning up oil spills. The winning team developed a solution that was four times better than the industry standard, Bunje said.

In October 2013, the X Prize organization announced a commitment to launch three more ocean X Prizes by 2020. The organization also launched the Ocean Ambassador program on its website to get the public involved in the development of new prizes.

"By 2020, we could move away from an unhealthy state and be on an unstoppable path to healthy oceans," Bunje said.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing ocean photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.