Greatest Mysteries: What Makes a Scientist?

Editor's Note: We asked several scientists from various fields what they thought were the greatest mysteries today, and then we added a few that were on our minds, too. This article is the first of 15 in LiveScience's "Greatest Mysteries" series to run each weekday.

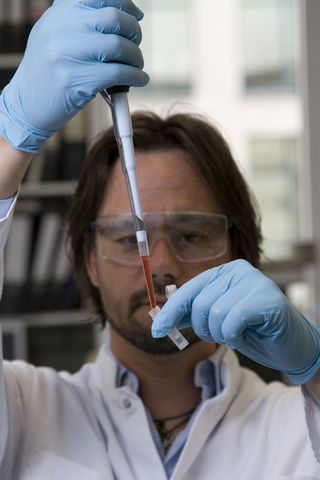

The scientist's job is to figure out how the world works, to "torture" Nature to reveal her secrets, as the 17th century philosopher Francis Bacon described it. But who are these people in the lab coats (or sports jackets, or suits, or T-shirts and jeans) and how do they work?

It turns out that there is a good deal of mystery surrounding the mystery-solvers.

"One of the greatest mysteries is the question of what it is about human beings—brains, education, culture etc.—that makes them capable of doing science at all," said Colin Allen, a cognitive scientist at Indiana University.

Few scientists have turned the microscope (or brain scanner) back on themselves. So even though the scientific method—with its hypotheses, data collection and statistical analysis—is well documented, the method by which scientists come to conclusions remains largely hidden.

"If we could understand scientifically what makes a scientist, this would potentially feed back on science itself and accelerate scientific progress," Allen said.

A curious development

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two vital ingredients seem to be necessary to make a scientist: the curiosity to seek out mysteries and the creativity to solve them.

"Scientists exhibit a heightened level of curiosity," reads a 2007 report on scientific creativity for the European Research Council. "They go further and deeper into basic questions showing a passion for knowledge for its own sake."

According to one definition, curiosity is a sensitivity to small discrepancies in an otherwise ordered world. Studies have shown that curious people have a mixture of seemingly conflicting desires: they seek novelty and strangeness and yet they also want everything in its proper place.

The curious scientist believes there is an order to the universe but is always looking for unexpected data points that will test the accepted theory.

Creative tool kit

To resolve the conflict between data and theory, a scientist often has to think outside the box and approach the problem from different angles.

Max Planck, one of the fathers of quantum physics, once said, the scientist “must have a vivid and intuitive imagination, for new ideas are not generated by deduction, but by an artistically creative imagination.”

To understand this scientific creativity, some philosophers of science have made an analogy with child development. The idea is that a scientist uses the same strategies for investigating the world as an infant does discovering his/her surroundings for the first time.

"This makes scientific abilities seem like part of a very basic 'tool kit' that is not specific to science itself," Allen said.

It harkens to something the astronomer Carl Sagan once said, "Everybody starts out as a scientist. Every child has the scientist's sense of wonder and awe."

Unwilling subjects

But others disagree with this universal scientific mind. They believe that scientists have special abilities that set them apart.

Discovering these abilities may be hard, Allen thinks, as many scientists will be reluctant to reveal them and would prefer to preserve the mystery of creativity, fearing that if it became an object of study it would lose its magic.

But for Allen, this is all part of a bigger question of what lies behind anyone's behavior.

"We are only just beginning to understand how the traits of organisms, including ourselves, aren't the fixed products of either genes or of environment/culture, but each of us is the product of a continual interactive process in which we help build the environments that in turn shape us," he said.

A brain doesn't work in a vacuum. It makes decisions that alter its surroundings, which in turn affects later decisions. Unraveling how this constant feedback loop works in a scientist will not be easy to do with current brain imaging techniques such as fMRI.

"As long as our best technology for seeing inside the brain requires subjects to lie nearly motionless while surrounded by a giant magnet, we're only going to make limited progress on these questions," Allen said.

- The Most Popular Myths in Science

- The Greatest Modern Minds

- Life's Little Mysteries

Most Popular