Kansas Grass Fires Seen from Space

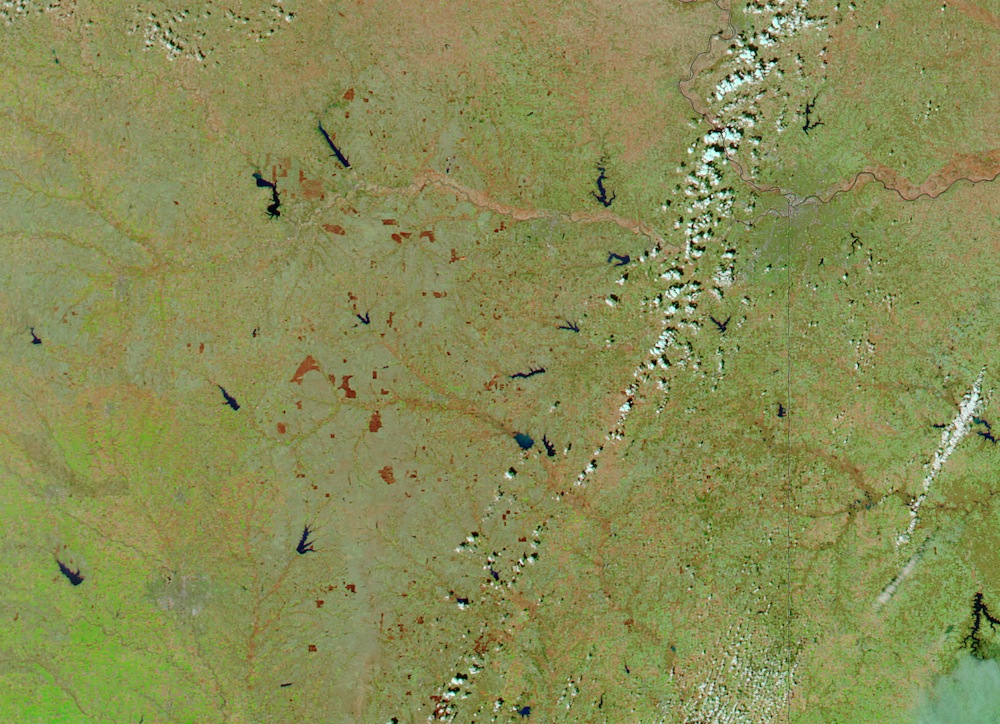

A new satellite image shows grass fires scattered like seeds across the Kansas prairie.

And in fact, these fires are a bit like seeds, in that they are a crucial part of the prairie ecosystem.

"We can’t have prairie without fire," Jason Hartman of the Kansas Forest Service told NASA's Earth Observatory, which released the satellite image today (April 9).

The Flint Hills of eastern Kansas are the site of most of the remaining tallgrass prairie in the United States. These rippling grasslands represent only 4 percent of the 170 million acres (688,000 square kilometers) that once blanketed the plains. The flint rock of eastern Kansas kept early farmers from tilling the land and saved the grass, according to the state's Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. [Images: The Unexpected Beauty of Tallgrass Prairie]

The prairies evolved to flourish after lightning-sparked fires, a fact humans have long taken advantage of. The Native Americans who once hunted this region lit fires to burn off dead vegetation, encouraging new growth that attracted bison and other large game. Modern ranchers also use controlled burns to clear soil for younger, more nutritious plants for their cattle, Earth Observatory reported.

Spring is controlled fire season at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. According to the National Park Service, prescribed burning was going on March 28th and March 29th, 2014. This image, snapped by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite, was acquired March 31. Red areas are burn scars from recent fires.

Tallgrass prairies may seem dull and undifferentiated to the untrained eye, but they're actually a complex and diverse ecosystem. About 80 percent of prairie vegetation is grass (40 to 60 species), with the remainder made up of more than 300 species of wildflowers, plus trees, scrubs and lichens, according to Live Science's Our Amazing Planet. The roots of these plants form tangles deep in the prairie sod, enabling early settlers to cut bricks from the soil. And these plant communities support more than 400 species of birds, 53 species of reptiles and 28 species of amphibians.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In March, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service placed one of these species, the lesser prairie chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) on its list of threatened wildlife. The prairie chicken, actually a grouse, is identifiable by its yellow head and red, puffy neck. It has lost more than 80 percent of its habitat to human development, including ranching, wild farms and oil and gas drilling.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.