Deep-sea Fish Inspire Robotic Feeding Model

This Research in Action article was provided to Live Science in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Deep in the ocean's twilight zone, dragonfish look like creatures crafted for a Hollywood "B" movie. Large eyes, oversized jaws and fang-like teeth mark the heads of these 20- to 40-cm long fish. To attract prey in their shadowy world, dragonfish dangle a glowing, whisker-like barbel from their chins. Dazzled by the lure's light, crustaceans and plankton are an easy catch.

While the mechanics behind the catch seem straightforward, researchers don't know exactly how dragonfish ingest their prey. Because the fish live at depths up to 1,500 meters, field studies remain a challenge. In the past, scientists used comparative analysis and computational modeling to better understand the feeding mechanisms of these fish. While these methods produced a large amount of data and provided an important foundation to understand feeding, they limited the kinds of questions researchers could answer.

As a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard University, Christopher Kenaley wanted to develop a less cumbersome and more realistic way to study how deep-sea fish feed. So, he and Harvard colleague George Lauder set out to build a 3-D robotic model of a dragonfish. However, the lack of live feeding data presented a challenge.

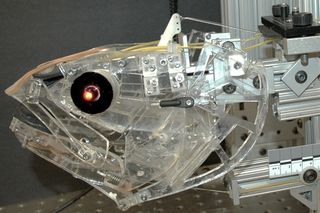

Kenaley and Lauder decided to look at how other species feed. Among the roughly 35,000 species of fish, suction is the predominant feeding mechanism. One of the best examples available is the large-mouthed bass. With plenty of live feeding data, the researchers constructed a 3-D robotic model of the bass, nicknamed "Bassbot."The model includes acrylic glass bones and electromagnetic motor muscles covered with a very thin latex skin.

One of Bassbot's critical advantages is the ability it gives the researchers to reproduce experiments. "Moving water is a complicated event and the model provides details on how this occurs and does so consistently," explains Kenaley. "With the model we can quickly assess discrete contributions of any one part of the fish head. This is hard to do with a live animal."

Kenaley views the Bassbot studies as a "stepping stone" to a deep-sea fish research program: "The robot seems like a cost-effective way to study [them]."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.