Native Americans along the Pacific Coast and aboriginal Siberians may have both originated from populations living on the land bridge now submerged under the Bering Strait, a new language analysis suggests.

The language analysis, detailed today (March 12) in the journal PLOS ONE, is consistent with the notion that ancestors to modern-day Native Americans were stuck in the region of the Bering Strait before making their way into North America. [Photos: Amazing Creatures of the Bering Sea]

Out-of-Asia?

Exactly how Native Americans first entered North America has been hotly debated. In one theory, people crossed the Bering Strait and rapidly colonized North America about 15,000 years ago.

But another theory, called the Beringia standstill hypothesis, proposes that people lived in and around the Bering land bridge between 18,000 and 28,000 years ago, when glaciers covered much of North America and the region wasn't submerged under water.

In that scenario, the region's shrubby trees, woolly mammoths and other big game allowed humans to eat and keep warm for millennia during the last glacial maximum, when trees for making fires were scarce everywhere else in the far north. Only when the glaciers in North America melted did people colonize the continent's interior via ice-free passageways, according to the theory.

Language family tree

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mark Sicoli, a linguist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and his colleague Gary Holton, a linguist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, wanted to see whether language origins could shed any light on the history of the these ancient migrations.

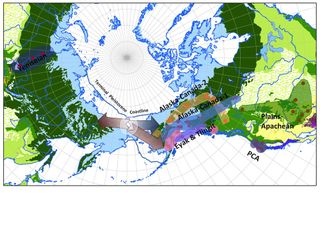

The team collected data on sounds and word structure from languages spoken on either side of the Bering Strait. One family of languages, known as Yeniseian, encompassed two languages spoken along the Yenisei River in central Siberia. The other group, known as Na-Dene languages, covers 37 languages spoken largely along the Pacific Coast of North America, including several Alaskan languages and Navajo.

Many of these languages are either extinct or extremely threatened: For instance, the Yeniseian language known as Ket is thought to have only 50 speakers, Sicoli wrote in an email.

Using a computer program, the team was able to model how all the languages were related to one another and compare that with the different models of how the languages might have dispersed.

Out of Beringia

The ancestral homeland for both groups likely originated somewhere in Beringia, the region in and around the Bering Strait, the analysis found. By contrast, a model in which speakers moved out of central or western Asia, which would mean that Yeniseian branched off from earlier languages before Na-Dene speakers dispersed in North America, didn't fit the data nearly as well.

The language tree suggested that Na-Dene speakers likely emerged early in North America and spread out later on, with Yeniseian speakers likely back-migrating westward into Siberia later.

Combined with ecological and genetic evidence, the findings support the notion that the ancestors to Native Americans settled in the Bering Strait region for a while before migrating into North America.

"We have three sources of information that support a similar picture, with the linguistic analysis supporting a Dene-Yeniseian homeland in Beringia," Sicoli said.

There are some limitations to the analysis: The model can't say exactly when different languages diverged from one another.

"There are ways to model time-depth, but it's a bit dicey. We are hoping to be able to work toward this in the future," Sicoli said.

However, most of the events they are studying likely happened around 10,000 years ago, and as such, the new finding doesn't directly address migrations during the last glacial maximum, John Hoffecker, an archaeologist and paleoecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

"Since it postulates a center of dispersal out of Beringia, it is, in a way, a second, and brief, standstill model, or 'Out of Beringia 2,'" Hoffecker said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.