Why a Recent Mammography Study is Deeply Flawed (Op-Ed)

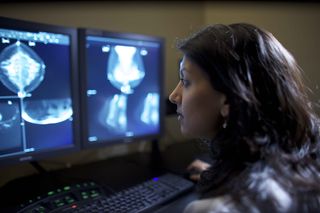

Dr. Mitva Patel is a breast radiologist at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Women questioning the value of screening mammography based on a recent study published in BMJ (formerly British Medical Journal) should pause and look more closely at the data. Medical societies and breast cancer specialists across the nation agree: the data is flawed and misleading.

There is no question that screening mammography saves lives.

More than 200,000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer every year. Mammograms aren't perfect, but they are still the best tool we have to find cancers early when patients have the most options for treatment. About 80 percent of the time mammography detects breast cancer, and the cancers that are found through mammography alone are typically small (averaging 1.0 to 1.5 centimeters). The average size of a breast cancer detected on physical examination is 2.0 to 2.5 cm. Only 10 percent of invasive cancers 1 cm or smaller have spread to lymph nodes, compared to close to 35 percent of those 2 cm in size — and cancers that have spread to lymph nodes are more likely to be lethal.

Flawed mammography data

The Canadian National Breast Cancer Screening Study (CNBCSS) — which served as the basis for the February 2014 BMJ paper — has been publicly denounced as a non-reputable source of data by professional medical organizations such as the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging.

This is for many reasons, including that the trial used second-hand mammography machines, with outdated and inaccurate technology. Images were compromised by "scatter," which makes all the breast radiologic images appear cloudy and the cancers difficult to see. Technologists who produced the data for the study were not taught proper positioning of the breast, resulting in missed cancers, and CNBSS radiologists involved in the study had not had proper training in mammographic interpretation. Would you want a radiologist who typically analyzes images of the stomach to interpret your mammogram?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the BMJ manuscript, only 32 percent of cancers were detected by mammography — an extremely low number indicative of the low-quality of mammographic images that were gathered. The study's authors used that result to support the conclusion that breast mammography is not valuable. At least two thirds of the cancers should have been detected with mammography alone had the study been accurate.

In addition, non-randomized placement of patients into groups for this study (i.e. screening versus no screening) most likely resulted in more women with advanced breast cancers being assigned to the screening arm of the study, which guaranteed more deaths among the screened women than those in the control group. This study violated the No. 1 rule of conducting clinical trials: To be a valid, randomized, controlled clinical trial, investigators must assign each participant to a study group at random to avoid skewing the data. Nothing can, or should be known, about those participants until they have been assigned to one of the study groups.

In this study, every participant underwent a clinical breast exam by a nurse, so physicians involved in the study knew if the women had breast lumps or enlarged lymph nodes under the armpits — often a sign of advanced (and less treatable) disease.

No "routine" breast cancer

I'm part of a sub specialized breast cancer team based the Stefanie Spielman Comprehensive Breast Center at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. We stand behind the American Cancer Society's recommendation that women age 40 or older have a screening mammogram every year. Women under age 40 with a strong family history of breast or other cancers may want to talk to a physician about their personal risk and benefits of genetic testing.

Because every woman's breast tissue is different — particularly as women age and hormone levels change — physicians rely on advanced diagnostic imaging tools like 3D mammography (tomosynthesis), ultrasound and breast MRI to pinpoint areas of concern with more accuracy and avoid taking invasive measures unless absolutely necessary.

As caregivers, our No. 1 goal is to eradicate each patient's breast cancer — but we also want to alleviate the fear and anxiety that comes with a breast cancer diagnosis by providing knowledge and a comprehensive, personalized, care plan that fits each patient's specific needs.

One in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lives — but the disease is highly treatable when caught early. I urge women to talk to their doctors about screening mammography; take the time to understand your family medical history; and learn your own personal risk for breast cancer.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular