Ocean Debris Leads the Way for Castaway Fisherman (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The fisherman who washed up on the Marshall Islands last weekend was very lucky to have stranded on a remote beach there.

The currents in the Pacific Ocean would have inevitably taken him into the great garbage patch of the North Pacific, where he could then have been floating for centuries to come.

The castaway - Jose Salvador Alvarenga, a fisherman from El Salvador - reportedly left Mexico in November 2012. He and his friend Ezequiel only planned for a short a fishing trip, but he ended up alone in his boat in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

His friend died about a month into the journey and Mr Alvarenga apparently survived on a diet of fish, birds and turtles, and by drinking turtle blood and rainwater.

Castaway Jose Salvador Alvarenga describes his ordeal.

Drifting westward

In the tropical Pacific, the trade winds create some of the strongest currents in the world. These currents move water, and with it plastics, plankton and castaways, westward.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

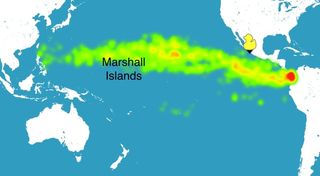

Some have cast doubt on the authenticity of Mr Alvarenga’s story but my research website adrift.org.au shows that flotsam that starts off the west coast of Mexico will pass through the Marshall Islands within 14 to 20 months.

This agrees well with how long Mr Alvarenga says he had to live on his boat, feeding on fish, birds and turtles.

The circulation pattern of the Pacific Ocean therefore seems to vindicate his claims of being lost at sea for so long. The tropical Pacific is also known for its richness in marine life, with plenty of fish and bids so he would have had access to plenty of food.

Lucky to find land

Although Mr. Alvarenga is not to be envied for his trip, he was lucky in one way. The Marshall Islands are tiny atolls in a vast ocean. Stumbling upon a beach in that area is like finding a water well in the outback of Australia.

My website adrift.org.au shows that, if his boat had not been thrown on a remote beach in the Marshall Islands, it is likely that it would have continued moving westward towards the Philippines.

But before reaching the Philippine coast, the currents would have taken him on a giant U-turn, northeastward and back into the central Pacific.

Caught in the rubbish

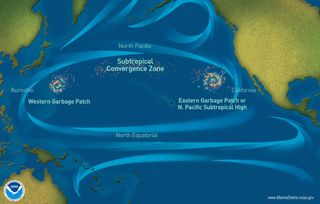

In the end, it is very likely that his boat would have ended up in the great garbage patch of the North Pacific.

This area, roughly between Hawaii and the California coast, is where much of the plastics, ghost nets and other floating debris that people throw in the ocean ends up.

The garbage patches (there’s five of them in the world, two in the Pacific, two in the Atlantic and one in the Indian Ocean) are the sinkholes of the ocean. Water at the surface slowly sinks to hundreds of meters depth. Everything that’s too buoyant, like plastics or fishing boats, stays behind for centuries to millennia.

The existence of these garbage patches is a disgrace. But unfortunately, it will be very hard to clean them up.

Most of the plastics in the patches is very small, roughly the same size as some of the plankton. There are currently no viable plans to remove the plastics but keep the plankton. Let alone do it in an environmentally sustainable way, without using enormous amount of dirty diesel to power a fleet of ships.

That is why the focus of the marine plastic problem should not be about cleaning it up, but about preventing the plastics from getting in the ocean in the first place.

Drifting buoys

Much of what we know of the surface ocean circulation comes from buoys that, just like plastic or castaway fishermen, drift with the currents.

But the buoys have an added tracking advantage. They have GPS and a satellite telephone, and send short text messages with their position every six hours. So the buoys are like twitter feeds from the ocean.

Most of the bouys also end up in the garbage patches. Oceanographers like me use the trajectories of the buoys to piece together how water would move from one location to the other.

It is important to understand how heat, nutrients, fish and plastics move through our ocean basin.

And, as an interesting side to our research, it also helps understand what has happened to the poor fishermen who get adrift.

Erik van Sebille receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular