Facial-Recognition Tech Can Read Your Emotions

If someone is described as "smiling, but not with their eyes," that person is likely faking the smile. But what does that mean, exactly? And how can one tell a real grin from a fake one?

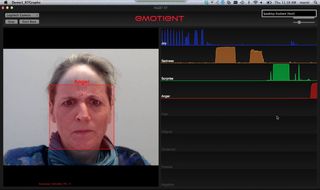

New software by California-based company Emotient can do just that. Using a simple digital camera, Emotient's software can analyze a human face and determine whether that person is feeling joy, sadness, surprise, anger, fear, disgust, contempt or any combination of those seven emotions.

"There's often a disconnect between what people say and what people do and what people think," said Marian Bartlett, co-founder and lead scientist at Emotient. The company's software, called Facet, can reconnect those dots by accurately reading the emotions registering on a person's face in a single photograph or video frame. All it needs is a resolution of at least 40 by 40 pixels. [Smile Secrets: 5 Things Your Grin Reveals About You]

Using Facet on a video sequence produces even more interesting results, because the software can track the fluctuations and strengths of emotion over time, and even capture "microexpressions," or little flickers of emotion that pass over people's faces before they can control themselves or are even aware they've registered an emotion.

"Even when somebody wants to keep a neutral face, you get microexpressions," Bartlett told LiveScience. That's because the human body has two different motor systems for controlling facial muscles, and the spontaneous one is slightly faster than the primary motor system, which controls deliberate motion. That means microexpressions will slip out — and as long as they appear on a single frame of video footage, Facet can recognize them, the company says.

The software can also pick up on other subtle facial signs that a human might miss. In the case of "smiling, but not with your eyes," Bartlett explained that when people smile sincerely, a muscle called the orbicularis oculi, also known as the "crow's feet muscle," contracts, creating the wrinkles at the eyes' edge that are sometimes called "crow's feet." In these types of cases, the software does need images clearer than 40 pixels, but the required resolution is still within a common webcam's capabilities.

Medical applications

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, what are some uses for software that can identify human emotions based on facial expressions? Facet's applications are incredibly far-reaching, from treating children with autism to play-testing video games.

Recognizing other people's emotions based on their facial expressions is a challenge for many people who have an autism spectrum disorder, particularly children. As a research professor at the University of California, San Diego's Machine Perception Lab, Bartlett has been studying the use of facial-recognition software to help people with autism for several years. [5 Controversial Mental Health Treatments]

Using an earlier version of Facet's software, for example, Bartlett and her colleagues created a game in which players are asked to mimic the facial expressions of a cartoonish character on the screen. Using Emotient's software, the game assesses the player's success in recreating that expression, and returns a score.

This game helps children with autism recognize other people's emotions through their facial expressions, as well as teaches them how to make facial expressions that express their own feelings.

"Facial-expression recognition and facial-movement recognition are very closely intertwined," said Bartlett. "That's the way the brain works. It's not that you have one brain that does the recognition and one that does movement; it's a network that feeds on itself."

Building that facial muscle memory also helps players recognize their own emotions, and creates a sort of emotional memory, Bartlett added.

"If you move your face into a happy configuration, you tend to feel happier," Bartlett said. "People can manipulate this by putting a pencil in their mouth: It makes you smile, and you get autonomous nerve system memory. It helps with empathy: You see it, you do it and you feel it, and it helps jump-start the whole social empathy system."

Other types of games could benefit from emotion recognition as well. Imagine a pet simulator, in which a virtual dog or cat reacts to the player's expressions: is happy when that player is happy, sad when the player is sad, upset when the player is angry.

Even if it's not built into the game itself, emotion recognition could help designers play-test their games. If players are getting too angry at a certain level of the game, the designers might want to make that part easier. If players feel confusion — an emotion recently added to Facet's detection capabilities — the designers might need to add a tutorial.

However, there is one possible use Emotient has no interest in exploring. "We're staying away from deception applications," said Bartlett.

It's easy to speculate on how software that can recognize the emotions behind human facial expressions, and even register fleeting microexpressions, could be used for covert purposes.

Instead, Bartlett said Emotient is now working on, among other things, the software's potential for identifying and treating depression. It's back to the idea of "smiling, but not with your eyes" idea: Depressed people often smile without activating their "crow's feet" muscle, not because they're trying to hide something, but because they have difficulty feeling any emotion at all.

Depression is often difficult to diagnose, and even more difficult to treat, but with Facet, doctors could make more accurate depression diagnoses, and also determine whether their patients are responding well to their medication, Bartlett said.

Email jscharr@technewsdaily.com or follow her @JillScharr. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular