A deep-sea voyage to drill more than a mile below the ocean floor could solve one of Earth's long-standing mysteries: how continents form.

An oceangoing research vessel, which sets sail in March, will venture to a chain of underwater volcanoes known as the Izu-Bonin arc, which stretches 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers) from Mount Fuji in Japan to the U.S. territory of Guam. The goal is to drill about 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) below the ocean floor, traveling more than 40 million years back in time to understand exactly how the beginnings of a continent underneath the volcanoes formed over time.

Mysterious formation

Though the continents may seem commonplace, Earth is "the only planet known to civilization that has them," said James Gill, a geologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who is going on the expedition.

Continents are made up of a thicker, lighter crust that sits above the denser, thinner oceanic crust. Oceanic crust is rich in the heavy elements, like iron and magnesium, found in the layer of solid, hot rock flowing beneath the crust and known as the Earth's mantle, said Cathy Busby, a geologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who is also going on the trip. Water then fills in the troughs created where the oceanic crust predominates, forming the oceans.

"You can think of the continents like ice cubes or icebergs bobbing in water," Busby said.

Although scientists understand where continents form — at locations where a tectonic plate is subducting, or diving back into the Earth's mantle — exactly how continents form isn't fully explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long trip

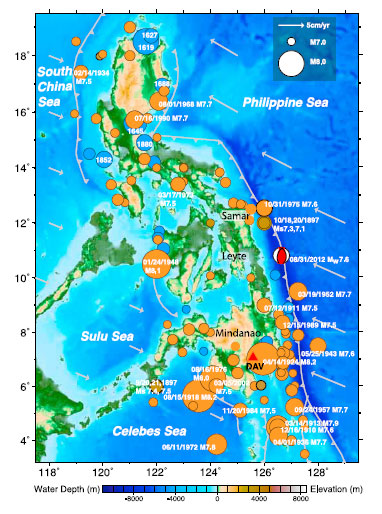

The sea vessel JOIDES Resolution will set sail from Keelung City, Taiwan, and head to a spot in the Izu-Bonin arc, part of the Pacific ring of fire or the circum-Pacific belt, a narrow zone of high volcanic and seismic activity in the Pacific where two tectonic plates meet.

For the next two months, a giant drill on the ship will carve out a circular portion of the sediment, going progressively deeper until it has gone through about 1.3 miles (2 km) of water and cored long, cylindrical sections of sediment from 1.4 miles (2.2 km) below the ocean floor.

The 30 researchers onboard will then spend 12 hours a day, 7 days a week analyzing the sediments, fossils and chemistry of the cores they bring up.

All along the arc, the Pacific plate is subducting under the Philippine Sea Plate and into the mantle, in a similar process to the one that formed the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot on Earth. The melting caused by the subduction has created a chain of underwater volcanoes above the plate's destruction, Busby said. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Trench]

This continent-forming process began about 52 million years ago. Over time, more and more crust formed at the edges of the growing continent, Gill said.

"The continent grows like an onion — it gets bigger and younger as you go to the outside" of the landmass, Gill told LiveScience.

Unanswered questions

The team hopes the core sediments will help paint an incredibly detailed picture of about 40 million years of continent-formation history.

In particular, they hope the process will help them understand why another string of volcanoes formed perpendicularly to the arc. One theory is that subduction spurs "hot fingers," or currents, to streak through the mantle, leading hot mantle rock to flow toward the plate and form the smaller, perpendicular volcanic chain.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.