Bedbugs: Facts, Bites and Infestation

Bedbugs lurk in cracks and crevices and they've been living on human blood for centuries. Though they aren't known to transmit disease or pose any serious medical risk, the stubborn parasites can leave itchy and unsightly bites. However, bedbugs don't always leave marks. The best way to tell if you have a bedbug infestation is to see the live, apple-seed-size critters for yourself. Unfortunately, once bedbugs take up residence in homes and businesses, they can be difficult to exterminate without professional help.

Appearance, lifestyle and habits

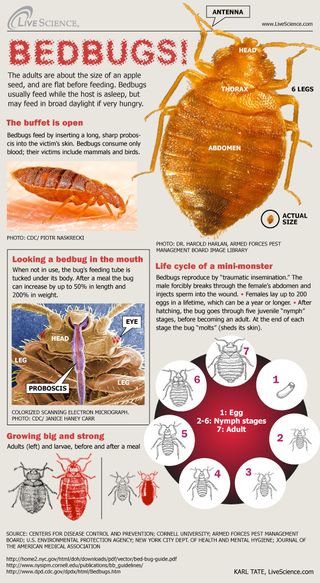

Bedbugs are flat, round and reddish brown, around a quarter-inch (7 millimeters) in length. The ones that typically plague humans are the common bedbug Cimex lectularius and the tropical bedbug Cimex hemipterus.

A few decades ago, bedbugs were somewhat of a novelty in developed countries. But since the early 2000s, infestations have become more common in places like the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Europe, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A 2013 study in the journal Nature Scientific Reports suggested that bedbugs have evolved ways to resist insecticides.

The creatures don't have wings and they can't fly or jump. But their narrow body shape and ability to live for months without food make them ready stowaways and squatters. Bedbugs can easily hide in the seams and folds of luggage, bags and clothes. They also take shelter behind wallpaper and inside bedding, box springs and furniture. The ones that feed on people can crawl more than 100 feet (30 meters) in a night, but typically creep to within 8 feet (2.4 m) of the spot its human hosts sleep, according to the CDC.

Bedbugs reproduce by a gruesome strategy appropriately named "traumatic insemination," in which the male stabs the female's abdomen and injects sperm into the wound. During their life cycle, females can lay more than 200 eggs, which hatch and go through five immature "nymph" stages before reaching their adult form, molting after each phase. [Infographic: Bedbugs: The Life of a Mini-Monster]

And it turns out, the pests may have favorite colors. Scientists conducted lab tests with bedbugs and found they sought out shelters, called harborages, that were red or black, while avoiding those denizens with shades of yellow and green. (The researchers say that changing the color of your sheets may be taking the finding too far.)

"We originally thought the bedbugs might prefer red because blood is red and that's what they feed on," study co-author Corraine McNeill, an assistant professor of biology at Union College in Lincoln, Nebraska, said in a statement. "However, after doing the study, the main reason we think they preferred red colors is because bedbugs themselves appear red, so they go to these harborages because they want to be with other bedbugs, as they are known to exist in aggregations."

As for steering clear of green and yellow? Those hues may resemble brightly lit areas, which bedbugs try to avoid, according to the researchers, who detailed their study April 25, 2016, in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded",function(){BZ.init({animationType:"filmstrip",contId:"bzWidget",catId:10654,keywordId:"",flowId:2278,pubId:36757});});

Bedbug bites

Bedbugs feed on the blood of humans (though some species have a taste for other mammals and birds, too) by inserting a sharp proboscis, or beak, into the victim's skin. The critters become engorged with blood in about 10 minutes, which fills them up for days.

The insects are most active at night, though they are not exclusively nocturnal. Bedbugs are attracted to warmth, moisture and the carbon dioxide released from warm-blooded animals, according to Purdue University. On sleeping human hosts, bedbugs often bite exposed areas of the body, such as the face, neck, arms and hands.

But looking for bedbug bites might not be the best way to tell if you have an infestation.

"A lot of people put a lot of import on looking at the bite and identifying it," Harold Harlan, an entomologist and a bedbug expert, told Live Science. "I've raised these things for 41 years and I cannot tell what is a bedbug bite."

Bedbug bites can look very similar to bites from other insects like mosquitos and fleas. People also have widely varying reactions to bedbug bites. Some people have little visible reaction to the insects' nibbling — they don't develop lesions or bumps or pustules at all.

The bites themselves don't usually pose any major health risk since bedbugs are not known to spread diseases, but an allergic reaction to the bites may require medical attention, CDC officials say. There have also been some strange cases linked to bedbug infestations. Researchers reported in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2009 that they treated a 60-year-old man for anemia caused by blood loss from bedbug bites. Another study published in 1991 in the Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology found that people with asthma might be more susceptible to allergic reactions from bedbug bites.

Excessively scratching the itchy, bitten areas also may increase the chance of a secondary skin infection. Antiseptic creams or lotions can be used to ward off infection and antihistamines can be used to treat the itching. And an infestation can take a psychological toll on those affected: People whose homes have been infested with bedbugs may have trouble sleeping for fear of being bitten in the night. There are also public health, social and economic consequences; office buildings and schools often have to close if they are dealing with a bedbug infestation.

Identifying and treating an infestation

If bites are unreliable markers of an infestation, how can you tell if you have bedbugs? Seeing live, moving bugs is the "gold standard," according to Harlan. If you can, you should collect some of those specimens in a closed container and get a professional to identify them.

You should look for traces of the insects in the folds of your mattresses, box springs and other places where they are likely to hide. You might be able to find their papery skins, which get cast off after molting and look like popcorn kernels but are smaller and thinner, Harlan said. They also leave small, dark-colored spots from the blood-filled droppings they deposit on mattresses and furniture. If you can touch the spot with a water-soaked towel and it runs a rusty, reddish color, you're probably looking at a fresh drop of bedbug feces, Harlan said.

Bedbugs often invade new areas after being carried there by clothing, luggage, furniture or bedding. The creatures don't discriminate between dirty and clean homes, which means even luxury hotels can be susceptible to bedbugs. The most at-risk places tend to be crowded lodgings with high occupant turnover, such as dormitories, apartment complexes, hotels and homeless shelters.

Getting rid of clutter may help to reduce the number of hiding places for bedbugs, but according to the CDC, the best way to prevent bedbugs is regular inspection for the signs of an infestation.

If you suspect an infestation, experts recommend finding a professional exterminator who has experience dealing with bedbugs. Sprayed insecticides are commonly used to treat infestations, and exterminators may also use nonchemical methods, such as devices to heat a room above 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius), a lethal temperature for bedbugs, according to the Mayo Clinic. Freezing infested items for a few days at temperatures below 0 F (-18 C) may also put bedbugs to permanent rest, according to the University of Minnesota. But you may have to throw out heavily infested mattresses and other items of furniture.

As for traps, these capture methods may not be full-proof for all bedbug species. Researchers have found that while both the common and tropical bedbug species have hairy feet, C. hemipterushas denser foot hairs, making this tropical insect an expert climber on slick surfaces. In the study, detailed on March 15, 2017, in the Journal of Economic Entomology, the researchers found that adult tropical bedbugs were much better at escaping traditional pitfall traps, which held onto most of the common bedbugs in the study.

Insecticides might also have their work cut out for them: Entomologists have known that the common bedbug has built up resistance to some typical insecticides such as those containing certain pyrethroid chemicals like deltamethrin, according to Entomology Today. Deltamethrin apparently paralyzes an insect's nervous system, according to Cornell University.

Turns out, C. lectularius is also forming a resistance to other insecticides, according to a study published online April 10, 2017, in the Journal of Economic Entomology. The researchers, from Purdue University, found that three out of 10 bedbug populations collected in the field showed much less susceptibility to chlorfenapyr, and five of the 10 populations showed reduced susceptibility to bifenthrin, according to a post on Entomology Today. The scientists defined "reduced susceptibility" as a population in which more than 25 percent of the begbugs survived after seven days of exposure to the particular insecticide.

"In the past, bedbugs have repeatedly shown the ability to develop resistance to products overly relied upon for their control. The findings of the current study also show similar trends in regard to chlorfenapyr and bifenthrin resistance development in bedbugs," study researcher Ameya Gondhalekar, research assistant professor at Purdue's Center for Urban and Industrial Pest Management, said in the Entomology Today statement. "With these findings in mind and from an insecticide resistance management perspective, both bifenthrin and chlorfenapyr should be integrated with other methods used for bed bug elimination in order to preserve their efficacy in the long term."

Additional resources

- New York Integrated Pest Management Program: Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Bed Bugs in Shelters and Group Living Facilities

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Bedbugs

- Purdue University Extension Service: Bedbugs

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.