How Cheeky: Fossil Fish Is Oldest Creature With a Face

A newly discovered fish fossil is the earliest known creature with what might be recognized as a face.

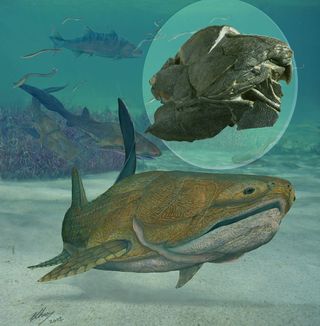

Entelognathus primordialis was an ancient fish that lived about 419 million years ago in the Late Silurian seas of China. The finding, detailed today (Sept. 25) in the journal Nature, provides a link between two groups of fishes previously thought to be unrelated, challenging long-held notions of how vertebrate faces evolved.

Nearly all vertebrates belong to the group of jawed vertebrates known as gnathostomes. Sometime in the past, the gnathostome family tree branched into two groups: cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) such as sharks and rays, and bony fish and four-limbed animals, including humans (Osteichthyes). [See Photos of Fish-Face & Other Freaky-Looking Fish]

Until recently, scientists assumed the common ancestor of gnathostomes was more similar to cartilaginous fish. This ancestor "would have looked something like a shark, devoid of armor and with a largely cartilaginous skull," said study leader Min Zhu, a paleontologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, in Beijing.

Bony goggles

To investigate, Zhu and his colleagues examined an Entelognathus fossil found in the remains of an ancient seabed known as the Kuanti Formation, near the town of Qujing, in Yunnan, southern China.

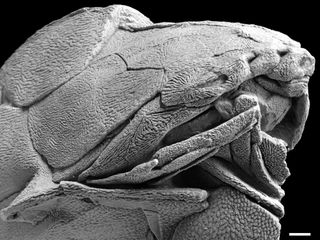

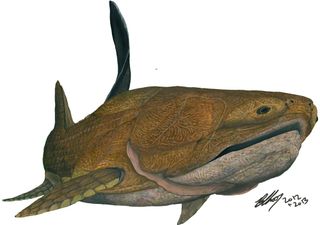

Analyses showed Entelognathus was nearly 8 inches (20 centimeters) long, with a heavily armored head and trunk and a scaly tail. Its eyes were tiny and set inside large "bony goggles," the researchers report. And despite having a jaw, it had no teeth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All known bony fishes have teeth, so the fossil adds to the mystery of how teeth originated, Young said.

Next, they compared the fossil with known jawed vertebrates, across a suite of physical characteristics. They also examined the facial bones in detail using an imaging technique called X-ray micro-computerized tomography.

At first blush, Entelognathus appears to be an ordinary placoderm, an extinct type of heavily armored fish. All placoderms discovered before now have sported simple jaws and cheeks, with only a few large bones making up their outer surfaces.

"But the original fossil of Entelognathus proved to be something far more bizarre and significant," Zhu told LiveScience.

Fish face!

On closer inspection, the fish possesses a complex arrangement of smaller bones known as a premaxilla and maxilla on its upper jaw, a dentary, or mandible, on its lower jaw, as well as cheekbones. These complex facial bones are characteristic of bony fish and land animals, including humans, making this bizarre-looking fish the most ancient animal with what humans would recognize as a face, Zhu said.

"This is certainly an amazing discovery, both because of its age [Silurian] and the morphology of the lower jaw," Gavin Young, a zoologist at Australian National University in Canberra who was not involved in the study, told LiveScience.

Scientists have long assumed placoderms and bony fish were unrelated, and that bony fish evolved their face bones from scratch. But the new finding suggests bony fish inherited their skulls from their placoderm ancestors, Zhu said.

The researchers further suggest that another extinct fish group called acanthodians, which resembled small sharks with big, bony fin-spines, actually belong to the same lineage as cartilaginous fishes, andprogressively lost their armored plates.

The discovery "throws a spanner" in the works of some long-held ideas about vertebrate evolution," Zhu said of the fish with a face.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 1:14 p.m. ET September 30, 2013, to correct a pronoun for the lead researcher, who is male.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.