Sun's Super-fast Plasma 'Conveyor Belt' Surprises Scientists

The sun's insides churn much more quickly than previously thought, a new study shows, a finding expected to improve predictions of solar storms that hurl charged particles at Earth.

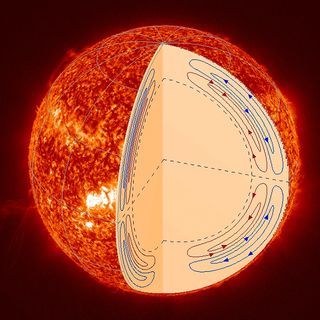

The flow of plasma — superheated, electrically charged gas — within the sun is more complex than scientists had believed, the study found. Further, this flow extends only half as deep as predicted, to roughly 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometres) beneath the solar surface.

"Our previously held beliefs about the solar cycle are not totally accurate, and ... we may need to make accommodations," lead author Junwei Zhao, a senior research scientist at the Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory at Stanford University, said in a statement. [Amazing Sun Storm Photos of 2013]

Tracking the conveyor

NASA and other space agencies keep a close eye on the sun through satellites such as the Solar Dynamics Observatory(SDO), whose observations were used for this study. The aim is to gain a better understanding of how the sun works.

Magnetic activity on the sun builds up from time to time, triggering eruptions known as coronal mass ejections — massive clouds of solar plasma that streak through space at 3 million mph (5 million km/h) or more. If these clouds strike Earth, they can short out electronics in satellites and ground systems.

The new study used the Stanford-operated Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager instrument aboard SDO to watch how waves of plasma move through the sun, just as seismologists study how seismic waves travel below Earth's surface. Radar images were taken every 45 seconds for the past two years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results revealed new details about meridional flow, a conveyor-belt like mechanism that transmits plasma throughout the sun. The gas moves on the sun's surface from the equator to the poles, and then heads into the sun's interior en route back to the equator.

Plasma patterns

The patterns scientists observed in the plasma waves allowed them to figure out how materials move through the sun.

"Once we understood how long it takes the wave to pass across the exterior, we determined how fast it moves inside, and thus how deep it goes," Zhao said.

Since plasma penetrates less deeply than previously believed, the gas is returning to the surface much faster than expected. Scientists also noticed the flow of plasma sandwiched between other currents; taking that into account will help with predicting the sun's activity, they said.

This year marks the peak of the sun's current 11-year activity cycle, which is known as Solar Cycle 24. Some computer models predicted a strong peak for this cycle, but it has turned out to be the weakest in a century. Inaccurate calculations of meridional flow could have contributed to these forecasts, the scientists said.

The report was published late last month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.