Personal Power: Bendable Organic Solar Cells

Researchers think new, flexible, lightweight organic solar cells may soon power everything from laptops to iPods.

The abundance of solar energy is a tantalizing alternative to the dwindling reserves of fossil fuels.

Until recently, the preferred material to harness that power has been solar panels made of silicon crystals.

Some success has come in powering homes and even cars. The widespread use of solar panels has been limited, however, by their cost to produce. Researchers believe they can overcome this barrier by cheaply producing an efficient organic solar cell.

The new organic cells are made from pentacene, which are sheets made of rings of hydrogen and carbon that occur naturally. Since engineers do not have to chemically manufacture them in the complicated process required for silicon panels, the organic cells are less expensive.

"To use a new technology it has to be economical," Bernard Kippelen, an electronics and computer engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told LiveScience.

In addition to being inexpensive, the cells have to be efficient. Efficiency is how much of the energy provided by the sun is transformed into electricity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

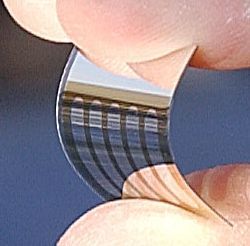

The new organic solar cells are light and flexible. Credit: Nicole Cappello and the Georgia Institute of Technology

Structure is one of the keys to that transformation. Patterns of silicon and oxygen repeat over and over again in the silicon crystals that comprise commercially available solar panels. Most naturally occurring materials, called organics, do not repeat their patterns, but pentacene does. That is why Kippelen and his colleagues have great hopes for the future of the organic crystal in solar cells.

Although the organic solar cells Kippelen and his colleagues developed are cheaper than silicon panels, they do not yet approach the 15 percent average efficiency of their commercially available silicon counterparts.

At present the organic versions have an efficiency of 3.4 percent, according to the details of the study in the Nov. 29 issue of the journal of Applied Physics Letters, but Kippelen hopes that figure will approach 5 percent in the near future.

"Every time we go back into the lab we increase purity and efficiency," Kippelen said. "Lately we have spent a lot of time modeling, and that teaches us what is required to improve efficiency."

Although Kippelen does not think these cells will provide energy on the scale of entire neighborhoods before they improve significantly, he does foresee ways to use the technology soon.

"These cells could power toys, or they could be made into little screens that you unfold and can recharge or replace batteries," said Kippelen.

Changing the sun's energy into electricity with materials that do not pollute the environment, and the hope that organic cells and solar power could one day replace fossil fuels as a main energy source, are why Kippelen believes this is important research.

"Solar power is appealing because there is plenty of sun and once we have an installation, the energy is free," Kippelen said.

Most Popular