Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a fatal disease that causes rapid degeneration of the cerebral cortex, or the outer layer of tissue surrounding the brain. It's a very rare disease, affecting only about 300 people in the United States annually. However, it is the most common of a family of diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which are named for the effect they have on the brain. TSEs cause tiny holes to form in brain tissue until it resembles a sponge when viewed under a microscope.

Other TSE diseases that affect humans are similar to CJD, but strike different parts of the brain, such as the cerebellum or the brain stem. These extremely rare hereditary diseases, such as fatal familial insomnia (FFI) and Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), are always deadly. Animals such as cows, sheep, goats and cats can also be affected by TSEs. The best-known form of the disease in animals is bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or "mad cow disease."

Causes

The approximately 300 cases of so-called "classic" CJD reported annually in the United States are grouped into three categories based on how a person acquired the disease. The most common category for the disease is sporadic CJD, which accounts for at least 85 percent of all cases in the United States, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Sporadic CJD appears in patients who have no known risk factors for the disease. Hereditary CJD, on the other hand, affects patients who have a family history of the disease or who test positive for a genetic mutation associated with CJD. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of CJD cases in the United States are hereditary, according to the NIH.

Lastly, acquired CJD is transmitted by exposure to brain or nervous system tissue infected with the disease. This type of CJD, which tends to affect those who undergo certain medical procedures, is extremely rare, accounting for less than 1 percent of all CJD cases since the disease was first described in 1920.

There is also another form of CJD that is separate from the classic categories of CJD. Known as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), researchers think this disease is connected to mad cow disease. First reported in 1996, all of the reported cases of vCJD are believed to have derived from the consumption of cattle products contaminated with BSE or from blood transfusions received from people contaminated with BSE, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).Unlike classic CJD, which tends to affect people over age 68, vCJD most commonly affects people under age 30.

Prion disease

CJD and vCJD — like all spongiform diseases in humans and animals— are commonly thought to be caused by prions, or proteinaceous infectious particles. Prions are different from other proteins found in the body in that they can reproduce on their own and can even become infectious.

Not all prions are deadly, however. Normal prions, known as sensitive prions (PrP-sen), are commonly produced by healthy cells, particularly inside of neurons in the brain, where it's believed they help control sleep patterns, according to the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center.

But resistant prions (PrP-res), known as abnormally folded proteins, are structured much differently than PrP-sen. Scientists aren't sure exactly how these mutant proteins reproduce, but they believe that when normal PrP-sen comes into contact with PrP-res, the PrP-sen is converted into PrP-res. In this way, the infectious protein multiplies itself, eventually forming long strands of proteins that are toxic to cells.

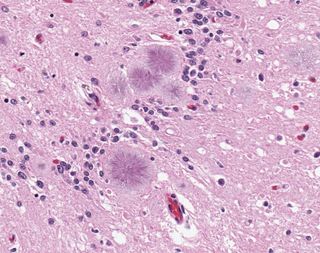

These long protein strands, known as amyloid fibers, destroy healthy brain cells, and other cells inside the brain — called astrocytes — eventually digest these dead cells. As the astrocytes make their way through the brain eating up the dead cells, they leave behind holes in the brain tissue.

In the majority of cases, the deadly prion PrP-res forms spontaneously in patients, and scientists are not sure why this mutation happens. In cases of hereditary CJD, the prion is believed to be an inherited mutation in the gene that codes for PrP-sen. And in cases of vCJD, the prion likely makes its way into the body when a person eats tissue infected with the killer protein.

Most of the research currently being conducted on CJD and its variants deals with discovering more about the cause of the disease, according to the NIH. Researchers are still trying to determine if the disease is, in fact, caused by a mutated prion and whether they can control the infectivity of this protein.

Further research is also trying to isolate why classic CJD appears most commonly in people over age 60 and what factors govern the appearance of the disease at this point in the life cycle, according to the NIH.

Signs & symptoms

The most common symptom associated with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is rapidly progressive dementia, according to the NIH. Early symptoms of the disease also include impaired memory, judgment and thinking, as well as impaired vision.

Those with CJD may also experience the following symptoms:

- Insomnia

- Depression

- Unusual sensations

- Severe mental impairment

- Involuntary muscle jerks (myoclonus)

- Blindness

- Inability to move

- Inability to speak

- Coma

While patients with CJD do no exhibit flu-like symptoms or fever, they may develop pneumonia or other infections. Severe infections of this nature may even lead to death, according to the NIH.

In patients with vCJD, symptoms manifest a bit differently. Not only does the disease typically affect young people (under age 30), early symptoms primarily tend to be psychiatric in nature.

Unlike Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease, which also cause degeneration of brain tissues, CJD progresses very rapidly, according to the NIH. Ninety percent of patients with the disease die within a year of diagnosis.

Diagnosis & tests

Diagnostic methods for CJD usually involve measuring the brain's electrical activity and getting images of the brain. EEG scans can detect characteristically abnormal brain patterns, and MRIs can reveal the damage present in the white and gray matter of the brain.

Cerebral spinal fluid collected through lumbar puncture will usually have a normal result, but with the exception of a slightly increased total protein count, according to the University of California, San Francisco. A tonsil biopsy may help diagnose vCJD, since lymphoid tissues tend to show evidence of the disease. However, this would not be readily detected in classic CJD patients, making the procedure less reliable for them.

Ultimately, only a brain biopsy or autopsy can reveal the spongelike damage in the brain and confirm a CJD diagnosis, according to the NIH. The brain of a vCJD patient shows microscopic prion protein plaques circled by a halo of holes (like a daisy) known as "florid plaques." These are rarely seen in classic CJD patients, according to the CDC. Since a correct diagnosis of CJD would not help the patient or reverse the course of the disease, a brain biopsy is often discouraged unless it's needed to rule out other possible mental disorders.

Most doctors will focus their diagnosis of CJD on ensuring the symptoms are caused by the disease and not, in fact, by a treatable form of dementia, such as chronic meningitis or encephalitis (brain inflammation), according to the NIH.

Complications

Most patients lapse into a coma as the disease progresses and the symptoms worsen. The cause of death is usually due to heart failure, respiratory failure, pneumonia or other infections, according to the Mayo Clinic.

About 90 percent of patients with spontaneous CJD die within a year of diagnosis, while others might die within just a few weeks, according to the NIH.

Treatments & medication

There are no treatments for CJD. According to the prion theory, once the prion is introduced into the body, it quickly distorts other proteins in the body, rapidly building up strands of "bad" proteins. A number of drugs have been tested to treat the disease, including steroids, antibiotics and antiviral medicines, according to the Mayo Clinic. However, treatment of the disease generally revolves around alleviating pain and other uncomfortable symptoms.

Opiate drugs may be prescribed to patients with CJD to help relieve pain, while clonazepam and sodium valproate may help relieve involuntary muscle jerks, according to the NIH. Patients require custodial care and a safe environment, either at home or in an institutionalized setting, while their mental functions worsen.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.