Elusive Dark Matter Pervades Intergalactic Space

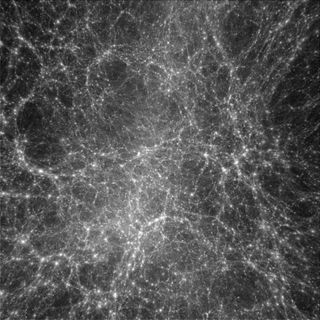

A group of Japanese physicists has revealed where dark matter is — though not what it is — for the first time. As it turns out, the mysterious substance is almost everywhere, drooping throughout intergalactic space to form an all-encompassing web of matter.

Dark matter is invisible: It doesn't interact with light, so astronomers cannot actually see it. So far, it has only been observed indirectly by way of the gravitational force it exerts on ordinary, visible matter. On the basis of this gravitational interaction, physicists have inferred that dark matter constitutes 22 percent of the matter-energy content of the universe, while ordinary detectable matter constitutes just 4.5 percent.

Shogo Masaki at Nagoya University and colleagues at the University of Tokyo’s Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe used computer simulations to model recent observational data of 24 million galaxies. By determining how light from the galaxies was bending slightly as it passed through space en route to Earth — an effect known as gravitational lensing — the researchers were able to work out the location of the dark matter that was bending it.

As detailed in a study published online Feb. 10 in The Astrophysical Journal, their model shows that dark matter extends from each galaxy far into intergalactic space, overlapping with the dark matter from adjacent galaxies to form a pervasive web that envelops the whole universe.

In fact, "intergalactic space" is a misnomer; the research shows that galaxies aren't contained regions with well-defined edges that are separated from one another by millions of light-years. Instead, they are composed of a central clump of ordinary, visible matter surrounded by a web of dark matter that extends "in an organized way halfway to the neighboring galaxy, so that the universe is filled with the material associated with … galaxies," the researchers wrote in a statement. [Gallery: The History and Structure of the Universe]

Furthermore, what we call "galaxies" are merely the peaks of this continuous matter distribution, the researchers explained.

The group mapped the distribution of dark matter over a distance of 100 million light-years from the center of each galaxy. "Its distribution," they noted, "is never random or uniform, but is well-organized."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But what is it?

Numerous dark matter searches are being conducted around the world. Scientists suspect the elusive material consists of WIMPs ("weakly interacting massive particles"), particles that are many times heavier than protons and only interact through gravity and the weak nuclear force.

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.