Indonesia Eruption: Why Are Volcanic Plumes So Dangerous?

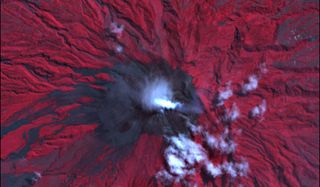

After a lull in activity, Mount Merapi in Indonesia sent a giant ash cloud barreling down its slope on Sunday (Oct. 31). Indonesian government officials continue to warn that the volcano is still dangerously active, and that nearby villages should continue to stay evacuated.

The showers of pale ash spewed from the volcano forced an airport in Solo, 25 miles (40 kilometers) east of Merapi, to temporarily shut down for more than an hour on Sunday, Transportation Ministry spokesman Bambang Ervan told news sources.

Airports, including Indonesia's national airline, Garuda Indonesia, were forced to reroute flights originally scheduled to fly over Yogyakarta and Central Java areas impacted by Merapi's ash plumes. Concerns that the volcanic dust would damage plane engines drove the route changes.

How does miniscule volcanic ash manage to ruin airplanes?

"Basically, planes and volcanic ash don't mix," Elizabeth Cory, a spokesperson for the Federal Aviation Administration, told Life's Little Mysteries. When ash is ingested into the engine, it creates problems for the plane, such as engine failure.

The thing that makes volcanic plumes so dangerous is that they look extremely similar to regular clouds, visibly and on radar screens. Even when ash isn't visible to the human eye, it can still pose a threat to aircraft because of the chemicals floating within volcanic plumes.

The ash particles that make up volcanic clouds contain powder-size to sand-size particles of igneous rock material that have been blown into the air by an erupting volcano. The tiny particles instantly melt when faced with the internal temperature of an in-flight jet engine, which exceeds 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The particles then stick to the turbine vanes, which control air flow and use its energy to propel the plane. This buildup of melted ash particles can stop an engine completely, leaving it dead in the air.

In lesser cases, airborne ash can cause electrical difficulties and damage flight control systems. There is also the issue of diminished visibility, which can make it impossible for pilots to see their flight paths if they fly through a volcanic plume after mistaking it for a regular cloud.

While it might not be as common as encounters with fog, commercial flights have bumped up against volcanic ash from some of the giant eruptions in the U.S, according to Boeing. In 1980, a 727 and a DC-8 encountered separate ash clouds during a major eruption of Mt. St. Helens in Washington. While there was damage to the crafts' windshields and other systems, both managed to land safely.

"The ash from the Mount St. Helens eruptions was one of the worst instances of a plume interfering with airplane traffic in the United States," Federal Aviation Administration spokesman Jim Peters told Life's Little Mysteries. "This current eruption in Indonesia seems to only be affecting Indonesian airlines."

Last April, a massive mushrooming cloud of ash from the eruption of the Eyjafjallajoekull volcano in Iceland resulted in the closure of major airports throughout the U.K. and Scandinavia. While Mount Merapi's current ash fall is much smaller than Eyjafjallajoekull's, Indonesia's location makes it more prone to volcanic activity.

In fact, after several volcanic-ash encounters by 747s near Jakarta, Indonesia, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) initiated a volcanic ash research effort in 1982. Since then, the Volcanic Ash Warnings Study Group has worked to standardize the information provided to flight crews about volcanic eruptions.

For these reasons, airlines have to stay on the safe side and cancel flights until the ash particles settle even if the airplane was to fly over an area thousands of miles away from the eruption site.