Icebreaker Ships Wrap Up Arctic Shelf-Mapping

A five-year mission to survey the Arctic continental shelf of North America using so-called icebreaker ships has come to a close, yielding important new data on the marine life and other key natural resources that are found there.

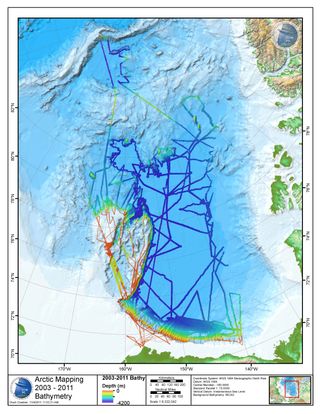

The project, a collaboration between the United States and Canada, collected scientific data to delineate the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the coastline, also known as the extended continental shelf (ECS). (One nautical mile is about 1.2 miles.)

The United States has an inherent interest in knowing, and declaring to others, the exact extent of its sovereign rights in the ocean as set forth in the Convention on the Law of the Sea. This includes rights to natural resources on and under the seabed, including energy resources such as oil and natural gas and gas hydrates; "sedentary" creatures such as clams, crabs, and corals; and mineral resources.

Preliminary studies indicate the U.S. ECS, including the Arctic Ocean areas surveyed, total at least 0.4 million square miles (1 million square kilometers), an area about twice the size of California. More data and analysis will help refine this estimate.

Breaking ice

The portion of the mission conducted this year during August and September was the fourth year to employ flagship icebreakers from both countries, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy and the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Louis S. St-Laurent. It traversed more than 5,600 total miles (9,000 km) over the Beaufort Shelf, Chukchi Borderland, Alpha Ridge and Canada Basin and reached more than 1,230 miles (2,000 km) north of the Alaskan coast. [Images: NASA in Arctic Frontier]

"This two-ship approach was both productive and necessary in the Arctic’s difficult and varying ice conditions," said Larry Mayer, U.S. chief scientist on the Arctic mission and co-director of the NOAA-University of New Hampshire Joint Hydrographic Center. "With one ship breaking ice for the other, the partnership increased the data either nation could have obtained operating alone, saved millions of dollars by ensuring data were collected only once, provided data useful to both nations for defining the extended continental shelf, and increased scientific and diplomatic cooperation."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

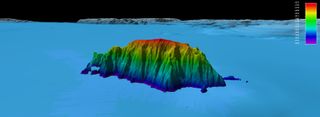

Scientists on board Healy used a multi-beam echo sounder to collect bathymetric data to create three-dimensional images of the seafloor. Scientists aboard CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent collected seismic data to determine the thickness of the sediments under the seafloor and to better understand the geology of the Arctic Ocean.

"As in previous Arctic missions, we obtained data in areas we were not entirely sure the ice would allow us to proceed, even with a two-ship operation," said Andy Armstrong, co-chief scientist on the Arctic mission and co-director of the NOAA-University of New Hampshire Joint Hydrographic Center. "This was especially true in the eastern part of the Canada Basin where some of the thickest Arctic ice is found."

Miles mapped

The missions' data also give scientists a baseline measurement of ocean acidification in the Arctic and offer a point of comparison for satellite estimates of ice extent and thickness.

Since the start of U.S. ECS work in the Arctic in 2003, Healy alone has mapped more than 123,000 square miles (320,000 square km) of the Arctic seafloor, or about the size of Arizona.

"These data provided high-resolution maps to help determine the outer limits of the U.S. ECS, while revealing previously undiscovered mountains, known as seamounts, and scours created by past glaciers and icebergs scraping along the ocean bottom 400 meters [1,300 feet] below the surface," Mayer said in a statement.

ECS work by the U.S. is not limited to the Arctic and includes areas in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic, Gulf of Alaska, Marianas and Line Islands, as well as areas off Northern California and northwest of Hawaii.