During Rare Southern Snowstorm, Scientists Spring to Action

When word came that Huntsville, Ala., would get more than a foot of snow in early January, it was big news.

For NASA scientist Walt Petersen, the last place he wanted to be was on his couch watching the Weather Channel.

"That's impossible for people like me," said Colorado-native Petersen, an atmospheric scientist at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville.

There are not many people like Petersen, however: He has high-tech NASA instruments at his disposal. They let him track the weather in real-time and see things in the clouds as they're happening. He knew a whopper winter storm was brewing.

"Everyone is always skeptical of snow forecasts in Huntsville because it doesn't always pan out," Petersen told OurAmazingPlanet. "We were pretty darn certain, we knew it was coming. There was no question."

The only question was how to best take advantage of the rare storm. Petersen rounded up his colleagues and they took their meteorological instruments, fresh off a snow study in Finland, and aimed them at the sky. Working under the cover of night the Friday before the storm, the team hustled to get the instruments in place. They double-checked everything on Saturday and then all eyes turned not toward the sky, but toward computer screens.

Over the next few days the scientists captured the most detailed dataset yet on snowfall in the Deep South . The data could one day help forecasters precisely predict a storm's intensity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All hands on deck

The scientists marshaled instruments from Huntsville's airport, the "instrument farm" at the University of Alabama in Huntsville and NASA. The goal was to model the storm from the ground all the way to the top of the clouds.

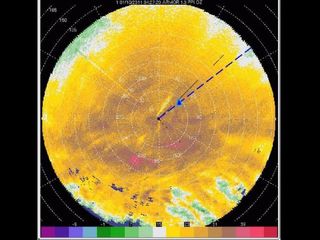

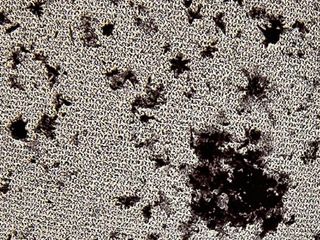

The team rolled out radars on trucks and dialed in radars at the airport. They set up normal rain gauges and rain gauges with lasers attached. The team turned on video cameras that can image the precipitation and radars that could tell if it was liquid or frozen. Still other instruments could pinpoint the location and size of snowflakes.

The alphabet soup of instrument names included ARMOR, 2DVDs, PARSIVELs and MAX, many of which were waiting to deploy to Oklahoma to study tornadoes. Their stopover in Huntsville could not have come at a better time.

Let it snow

The snowstorm hit late Sunday night through early Monday morning. A record 8.9 inches (22.6 centimeters) of snow fell on Huntsville, a new record for a 24-hour period and the most snow the city has seen since the "Storm of the Century" in 1993 .

As the data streamed in, team members were writing down notes and feverishly forming ideas to explain what they saw, Petersen said. As icing on the cake, the team witnessed a weather rarity.

"Low and behold we got some lighting flashes and thundersnow," Petersen said.

Thundersnow like a thunderstorm but with snow instead of rain is not common, certainly not in Huntsville. Justin Gatlin, a research associate at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, was one of the team members that pulled an all-nighter collecting data. The thundersnow did not disappoint.

"It was very impressive," Gatlin said. "We all get excited when we see thundersnow in the South."

The scientists saw that most of the lighting flashes started from an antennae tower. The bolts jumped into the clouds and then meandered 30 to 50 miles (48 to 80 kilometers) in layers, similar to lightning in squall line storms during Midwestern summers. Petersen said that whatever is going on with the process responsible for making the snow is also changing how the lighting propagates in the clouds.

But the answer to that question will have to wait for the careful analysis of all the data that is under way now that the snow is gone.

Future forecasts

The scientists want to use the data to build and refine models that can predict from space how hard it will rain or snow, and how much snow will stick. Such models could help southern cities brace for winter storms, or they could help resource managers in the drought-plagued West gauge how much snowmelt will be available to water crops in the spring.

But if the scientists are bold enough to put a number on how much snow will accumulate, they must be precise. Other weather models will build upon their snowfall model, so they need to be absolutely certain, Petersen said.

That number crunching will continue for some time, yet the effort has already exceeded expectations, considering it was a last-minute project.

"I thought, 'Oh man, here's an opportunity for us to collect a really great dataset,'" Petersen said. For a spontaneous research project in the middle of a southern city's biggest snowstorm, everything went off without a hitch.

"It all actually worked well, that was the funny thing," Petersen said.

- Image Gallery: World's Snow Cover Seen from Space

- Could This Frigid Winter Be a Record-Brrreaker?

- The Snowiest Places on Earth

Reach OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Brett Israel at bisrael@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @btisrael.