Oregon Preps for The Big One: Lessons from an Ancient Quake

As walls of water roared ashore, the people of the Japanese village of Kuwagasaki made a desperate run for higher ground. They watched from the hills as their town was consumed by floodwaters and fire. With possessions and homes destroyed, a call went out to provincial officials for wood to build temporary shelters.

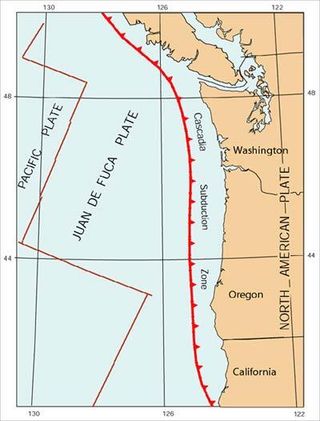

The tsunami that hit Japan in the early hours of Jan. 27, 1700, had traveled all the way across the Pacific, generated by a 9.0-magnitude earthquake on a fault that lurks in America's backyard: the Cascadia Fault, which stretches for almost 700 miles (1,100 kilometers) just off the West Coast from Northern California up to Canada.

That this massive quake ever occurred was discovered only in the last few decades, through painstaking scientific detective work on both sides of the Pacific. Ghost forests ? swaths of dead trees just north of the Washington-Oregon border ? offered one clue of a catastrophic event long ago. And as researchers learn more about the colossal, long-dormant power of the Cascadia Fault, public safety officials have taken notice.

Great Oregon ShakeOut

One day this week, exactly 311 years after the Cascadia Fault 's most recent rupture, more than 37,000 Oregonians dove under desks and tables, or clung to sturdy walls, ducking and covering for 60 seconds.

The exercise, the largest in state history, was a part of the first Great Oregon ShakeOut, an earthquake drill designed to prepare people for Cascadia's next big move. (The ShakeOut's catchphrase is easy to remember: "Drop, Cover, and Hold On.") California has conducted similar earthquake drills.

Althea Rizzo, the Geologic Hazards Program coordinator for Oregon Emergency Management, was one of the organizers of the ShakeOut, which has been planned as an annual event. She said that although the historic quake happened at around 9 p.m. local time, the drill was moved to 10:15 a.m. so school kids and businesses could more easily join in.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'm thrilled with the turnout," Rizzo said. "It's been going like gangbusters."

Three hundred people at her location the Eugene Public Works, a sprawling complex of buildings had signed up to take part, and Rizzo, reached on her cell phone just before the drill, was outside the break room where she'd be heading under the furniture in about an hour's time.

Rizzo would not be disappointed with the morning's proceedings. An hour or so post-ShakeOut, Rizzo told OurAmazingPlanet: "It went really, really well. We had people underneath desks and tables everywhere!"

While the drill lasted one minute, Rizzo said that if the Cascadia Fault ruptures, people are going to be hiding under tables a lot longer.

"The actual shaking will be between five and 10 minutes long," Rizzo said. That's because Cascadia's fault line known as a subduction zone , an area where one tectonic plate is diving beneath another is hundreds of miles long. "It takes between five and 10 minutes for it to break along the entire fault line," Rizzo said.

Cascadia's history

Brian Atwater of the U.S. Geological Survey has studied Cascadia's history exhaustively, and said it was important to mark the date Jan. 26, the anniversary of the fault's last dramatic move.

"There are good reasons that we mark anniversaries," Atwater said from his office at the University of Washington, "and the same goes for this one. It's a reminder of a hazard that doesn't make itself known very often."

The geologist added that, in terms of sheer power, the Cascadia Fault has few rivals around the globe. "The amount of movement that takes place on the fault takes centuries to build up," Atwater said. So when the fault does finally rupture, it unleashes hundreds of years of pent-up energy, producing a devastating earthquake.

He said that on average, the Cascadia ruptures roughly every 500 years, but the intervals between quakes can be as brief as 200 years or longer than 1,000.

Most recent data suggest there's about a one-in-10 chance the Cascadia will rupture in the next 50 years.

"One could happen here tomorrow, or it may take centuries for the next one to happen," Atwater said. "But you want to be prepared for it when it does."

Raising awareness

Rizzo said part of her job is to make sure people know about the risks and have emergency supplies and plans in place for an earthquake and ensuing tsunami.

"We've got 9 million people in the impact zone between Washington and Oregon," Rizzo said. To indicate the devastation a quake could cause, Rizzo pointed to Hurricane Katrina's effect on New Orleans.

"Just imagine New Orleans ? but from Northern California to British Columbia," Rizzo said. "I don't want to scare people. I want to empower them to take steps to make sure their families are safe."

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.