Science of 'Protein Origami' Unfolds

There's now a way to make "protein origami" — self-assembling shapes made of twisted molecular strands— a new study reveals.

The technology builds upon the advances of DNA origami, a technique that has been used to build box shapes, DNA scissors and other materials. Now, bioengineers have produced a single-stranded coil of protein that spontaneously sprang into a pyramid shape. While just an early demonstration, the technique could someday be used to make vehicles for drug delivery or to catalyze reactions.

"It is a piece of great work in the field of programmed biomacromolecular self-assembly," said chemist Chengde Mao of Purdue University in Indiana, who was not involved in the study. "The beauty of the strategy is its simplicity." [Biomimicry: 7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature]

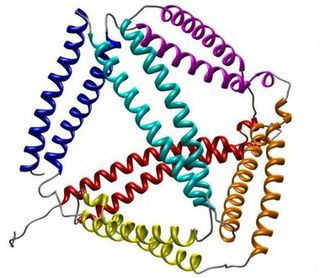

Proteins are the molecular building blocks that carry out a host of vital functions in cells. They are composed of long chains known as polypeptides, which coil and fold to form complex 3D structures.

The idea with protein origami is to create rigid segments that can self-assemble in a modular fashion, like LEGO bricks. The segments are "smart" materials, because they contain all the information for the final structure inside them.

For the bricks, researchers designed well-studied structures called "coiled-coil segments" — a combination of two or more helices that intertwine. They then made a chain of 12 of these segments stitched together on flexible hinges, which self-assembled into a pyramidlike shape known as a tetrahedron. Each edge of the tetrahedron was bounded by two of the segments.

"The shape is completely different from anything natural," said senior study author Roman Jerala, a synthetic biologist at the National Institute of Chemistry in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jerala and his colleagues confirmed the tetrahedron's formation using several kinds of microscopy. Each tetrahedron was only about 5 nanometers on an edge, about one ten-thousandth the width of a human hair.

Right now, it's just a proof of principle, Jerala told LiveScience. But ultimately, protein origami could be used to encapsulate drugs, for instance, to allow their controlled release. Or these structures could act as catalysts for reactions, much like enzymes in living cells.

Creating similar shapes using DNA origami is cheaper and easier to handle than proteins, said Paul Rothemund of Caltech, who was not involved in the study. But protein origami lets you make them much finer. "Making structures out of DNA is like building molecular structures out of DUPLO blocks [giant LEGOs]," Rothemund said, but "working with proteins, on the other hand, is sort of like working with adult LEGOs — they have a much smaller intrinsic resolution."

Scientists have created small objects out of proteins before, but these had to be symmetrical shapes, Jerala said. Using protein origami, "we can take natural elements and do something completely different that does not exist in nature," Jerala said. "Nature just didn’t explore all the possibilities."

The findings were detailed today (April 28) in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Most Popular