Baby Cured of HIV: What Are the Implications?

The announcement that a baby in Mississippi has been allegedly cured of an HIV infection could have implications for other HIV-infected infants, and perhaps even adults, according to experts.

But before researchers know for certain whether the baby's case might indeed affect others, a number of studies need to be done, some of which could be tricky to carry out, experts said.

First, researchers need to know if the baby in Mississippi has truly been cured of HIV.

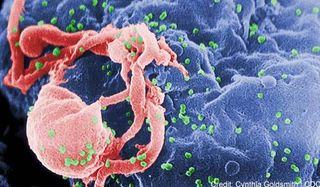

The baby, who was born to an HIV-infected mother, was treated with higher-than-typical doses of antiretroviral drugs 30 hours after birth. The baby tested positive for HIV during the first month of life, but the amount of virus in the infant's blood continually declined. Following 18 months of treatment, the baby and mother did not return to the doctor's office for some time, and as a result, the baby did not receive additional HIV treatment. When the baby did return about 10 months later and was tested for HIV, the tests came back negative, suggesting that there was no HIV in the baby's blood. When researchers used very sensitive tests for HIV, they found a small amount of HIV genetic material in the child, but the virus was not in an active form. This is what researchers refer to as a "functional cure" — the virus is present at low levels, but does not appear to cause harm.

However, because the virus has not been completely eliminated from the child's body, researchers said doctors must continue to follow the child to make sure what's left of the virus does not turn into an active HIV infection in the future.

"Will the few copies of the HIV virus that are still in cells in this child end up reactivating?" asked Dr. David Rosenthal, clinical director of the Center for Young Adult, Adolescent and Pediatric HIV at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System in New Hyde Park, N.Y. "We're going to have to wait and see."

Also, because the baby in Mississippi represents a single case, researchers don't know if the results can be replicated in another person. The researchers think that providing higher-than-usual doses of HIV drugs — doses intended for the treatment rather than the prevention of infection — soon after birth might have played a role in the baby's outcome. Future studies will be needed to test this protocol in other babies at high risk of HIV infection, experts said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, this could prove tricky, said Dr. Sten Vermund, director of the Institute for Global Health at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. That's because babies born to HIV-infected mothers can test positive for HIV without really being infected with the virus.

When babies are born to HIV-infected women, a small amount of the mother's blood can travel to the baby through the placenta, causing the baby to test positive for HIV, Vermund said. But to have a true infection, the virus needs to find its way inside the baby's cells, and replicate itself, Vermund explained. Knowing which babies really have an HIV infection, and which simply have HIV genetic material from their mother's blood, is not always easy to distinguish, Vermund said. "We're never quite sure who's infected at 30 hours," after birth, Vermund said. But detection of so-called RNA from the virus can be a sign that it's replicating, he said.

Future studies will also need to determine the risks of the treatment for babies, and whether those risks outweigh any benefits, Rosenthal said.

It's much more likely that the new findings will have benefits for babies than for adults, said Jerome Zack, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, who studies HIV infection. That's because the immune systems of babies differ slightly from those of adults, and the places where the virus "hides out" in the body could be different as well, Zack said. In addition, researchers typically know when a baby is infected with HIV — around the time of birth. However, in adults, the time of infection can be more difficult to pinpoint.

But doctors shouldn't rule out possible benefits for adults that come from the new findings in this baby, Zack said. First, we have to know how this possible cure happened, and then we can investigate whether it could be extended to adults. "Unless we know what that mechanism is, it's hard to say if we could definitely do that," Zack said.

Some people who were treated with HIV drugs very early in life reportedly have very low levels of HIV in their bodies, so low in fact, that the virus cannot be detected using standard HIV tests, Rosenthal said. It's possible that these people have been functionally cured of HIV as well, but since they have taken medications their entire life, it's not safe or ethical to have them stop the medications at this time, Rosenthal said. According to Vermund, earlier studies that attempted to take adults off of HIV drugs were not successful — the patients eventually needed to resume taking drugs to keep the virus in check.

Pass it on: A baby in Mississippi may have been cured of HIV, but more research is needed to determine how this case can apply to other people with HIV.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner, or MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.