Ancient 'Wave of Poseidon' Was Real Tsunami

SAN DIEGO – When the ocean rose up and saved a Greek town from a marauding Persian army nearly 2,500 years ago, renowned Greek historian Herodotus chalked it up to an act of the gods.

Yet new evidence suggests his account of divine intervention is firmly rooted in the earthly realm, and was actually a tsunami, according to a researcher who spoke here today (April 19) at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

"This is historical stuff, but you have to interpret it in a scientific way," said Klaus Reicherter of Germany's Aachen University, who studied geological evidence of the event.

Pressed Persians

Some 50 years after the 479 B.C. event, Herodotus wrote his account. "There came to be a great ebb of the sea backwards, which lasted for a long time," he wrote.

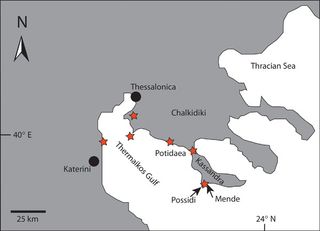

As the sea rolled back before them, the Persians surged forward toward modern-day Kassandra, a peninsula in northern Greece, to finish a town now called Nea Potidea. But before the invaders could reach dry land, their good luck turned sour.

"Then there came upon them a great flood-tide of the sea, higher than ever before, as the natives of the place say, though high tides come often," Herodotus wrote. The Persians were washed away and the town was saved.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Herodotus, like the villagers, saw the savior wave as the avenging hand of Poseidon, god of the sea, punishing the invaders for some offense, but Reicherter said the account accurately describes the phases of a tsunami. Tsunamis, he said, pose a far greater threat to the northern Aegean Sea region than many realize.

"We wanted to see if these historical accounts are correct and then try to get an assessment of the coastal areas — are they safe or are they not safe?" Reicherter said. The question is especially important in light of the region's popularity with beachgoers during summer months, he added. [History's Most Overlooked Mysteries]

Tsunami forensics

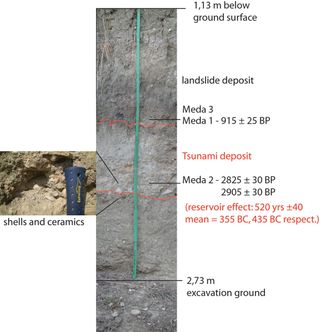

The telltale signs of tsunami action are buried not just in ancient texts but in the ground near the town described by Herodotus, where research teams uncovered layers of sand apparently carried far inland by a tsunami.

Furthermore, geological conditions in the area would have provided the ideal means for producing large waves, Reicherter told OurAmazingPlanet.

Earthquakes and landslides in the region, combined with a colossal, bathtub-shaped basin in the seafloor near the northwestern Greek coast, are capable of producing tsunamis from 7 to 16 feet (2 to 5 meters) high, according to models Reicherter and colleagues ran based on available data.

To further back their suspicions, the team dated shells found in the sand deposited by the tsunami. "They fit quite nicely: around 500 B.C., plus or minus 25 to 30 years," Reicherter said.

The research is part of an ongoing effort to hunt down and assess ancient tsunamis. The work can help show what areas are vulnerable to damaging waves and can help officials better prepare for the next big one, Reicherter said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Most Popular