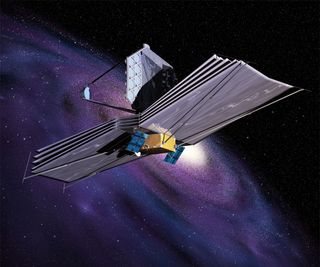

Future NASA Telescope Could 'Sniff' Air of Alien Planets

AUSTIN, Texas — The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could be used as a powerful tool that will enable astronomers to "sniff" the atmospheres of alien planets, according to David Charbonneau, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. With the James Webb Space Telescope's ability to stare uninterrupted at stars in infrared wavelengths, astronomers will be able to make unprecedented observations of alien worlds. "We can imagine how easy it would be to study different molecules and work out their atmospheric abundances," Charbonneau said today (Jan. 9) at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. According to Charbonneau, JWST essentially combines the best two properties of two existing workhorse NASA facilities that have made great strides in astronomy: The Hubble Space Telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope. "Hubble brought a large enough aperture that you could do spectroscopy, and you could really do it well," Charbonneau said. "Hubble has been revolutionary in exoplanet studies, but if I could change one thing, it would be the location of Hubble."

Hubble orbits a few hundred miles above Earth's surface, while NASA plans to put the $8.7 billion JWST — which is slated to launch in 2018 — about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away. The Spitzer Space Telescope collected data in infrared wavelengths, but had a small aperture and was not ideally suited for spectroscopy, he added. JWST, which is being billed as Hubble's successor, will combine both of these valuable capabilities. "JWST is an excellent platform for exoplanet spectroscopy," Charbonneau said. "There's an enormous number of different settings for each instrument, which can be used to tackle different problems."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.