Surprise Underwater Volcanic Eruption Discovered

An undersea volcano has erupted off the coast of Oregon, spewing forth a layer of lava more than 12 feet (4 meters) thick in some places, and opening up deep vents that belch forth a cloudy stew of hot water and microbes from deep inside the Earth.

Scientists uncovered evidence of the early April eruption on a routine expedition in late July to the Axial Seamount, an underwater volcano that stands 250 miles (400 kilometers) off the Oregon coast.

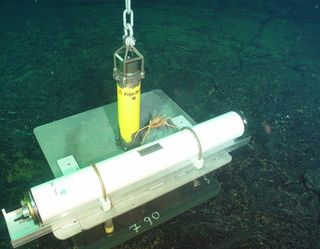

The discovery came as a surprise, as researchers attempted to recover instruments they'd left behind to monitor the peak a year earlier. When the researchers hefted a seafaring robotic vehicle overboard to fetch the instruments, the feed from the onboard camera sent back images of an alien seafloor landscape.

"At first we were really confused, and thought we were in the wrong place," said Bill Chadwick, a geologist with Oregon State University. "Finally we figured out we were in the right place but the whole seafloor had changed, and that's why we couldn't recognize anything. All of a sudden it hit us that, wow, there had been an eruption. So it was very exciting."

In addition to producing hardened lakes of blobby lava, in places more than a mile (1.6 km) across, the eruption changed the architecture of the region's seafloor hot springs.

"There are more vents, they're higher temperature, and there are microbes living in them that are usually deep in the crust that come up to the surface in these events," Chadwick told OurAmazingPlanet.

Eruption forecast

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Axial Volcano rises 3,000 feet (900 m) above the seafloor, the most active of a string of volcanoes along the Juan de Fuca Ridge, a plate boundary where the seafloor is slowly pulling apart.

Chadwick and colleagues have been keeping tabs on the peak since it last erupted in 1998. Thanks to a monitoring system they developed to measure the mountain's minute movements, the team forecast the volcano was due for another eruption sometime before 2014.

"So for me, it's a very exciting thing that this worked!" Chadwick said.

The instruments kept track of the movement of the seafloor, which very gradually inflates and deflates like a giant, magma-filled balloon, Chadwick said, collapsing suddenly after an eruption, and rising, in this case, by about 6 inches (15 cm) per year in the lead up to an eruption.

First long-term picture

Scientists have long known about the existence of subsea volcanoes, but information on their behavior is relatively sparse. Eruptions were first detected in the 1990s, and, although technology has improved, getting to the underwater peaks to study them is difficult.

Data from the Axial Seamount's recent eruption will provide the first long-term picture of a subsea volcano from one eruption to the next. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Chadwick said scientists are still trying to figure out how seafloor volcanoes differ from their terrestrial counterparts.

It could be it's easier to predict ocean eruptions, Chadwick said. It's possible that because the crust is thinner there, and magma is in ready supply, the mountains' slow inflations provide a good analogue for knowing when eruptions will occur. However, he cautioned that a single successful prediction wasn’t enough to forecast what the future holds.

"At Axial we've only seen this once, so we don't know for sure it's going to be reliable," Chadwick said. "So we'll certainly keep making these measurements, and hopefully be around to see what happens next."

- Video: New Vent Opens at Axial Underwater Volcano

- Video: Spectacular Collapse of Hawaiian Volcano Crater

- Image Gallery: Volcanoes from Space

Andrea Mustain is a staff writer for OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach her at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Most Popular