Pinatubo Flashback, June 9, 1991: Will the Rumblings Stop?

On June 15, 1991, the largest land volcano eruption in living history shook the Philippine island of Luzon as Mount Pinatubo, a formerly unassuming lump of jungle-covered slopes, blew its top. Ash fell as far away as Singapore, and in the year to follow, volcanic particles in the atmosphere would lower global temperatures by an average of 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius). Twenty years after Pinatubo, LiveScience is reliving the largest eruption in the modern era based on what we know now. Join us each day through June 15 for a blow-by-blow account of what happened. [Read all installments: June 7, June 8, June 9, June 10, June 11, June 12, June 13, June 14]

June 9, 1991: Pinatubo is showing no signs of settling down.

The volcano is throwing out enough ash today that, at times, curtains of the stuff fall to the ground. From the west side of the volcano, observers think they see pyroclastic flows moving down the flanks of the mountain. Pyroclastic flows are super-hot clouds of gas and rock, much like those that buried the residents of Pompeii in Italy in A.D. 79, and the sightings raise fears a major eruption has already started.

Amidst this volcanic chaos, American and Filipino scientists raise the emergency alert level to 5, a warning that an eruption is in progress. While this turns out to be a false alarm, it triggers wider evacuations from the area surrounding the volcano. By now, 25,000 people have been moved away from the area. [In Photos: The Colossal Eruption of Mount Pinatubo]

Under pressure, the scientists have to decide whether or not to evacuate Clark Airbase, the site of their own operational headquarters. Chris Newhall, the USGS leader of the volcano monitoring team, knows that if the 18,000 or so service members and civilians of Clark Airbase leave, it might be the end of U.S. military presence in the area.

"The pressure to 'get it right,' 'just in time' was intense," Newhall wrote in an email to LiveScience as the 20th anniversary of the eruption approached.

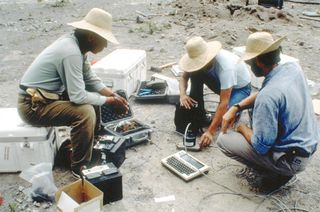

Through all of this, the research team is dependant on a hastily assembled seismic network, deployed over the course of a few months. In the future, seismic monitoring stations will be high-tech, digital, broadband-enabled affairs; but in 1991, they consist of a sensor and an ink-filled needle that jots out the Earth's movements on a roll of paper. There is no such thing as GPS, or the global position system of satellites that will one day allow geologists to monitor the deforming ground around a ready-to-blow volcano in real time. Without the Internet, the monitoring team relies on fax machines to communicate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Almost half of our seismic network was going through a small telephone exchange," recalled USGS scientist John Ewert. Before the big eruption comes, looters will steal the generator powering that exchange, taking that chunk of the network out of commission.

Tomorrow: A military retreat.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.