What's in Your Gut? 3 Bacterial Profiles Defined

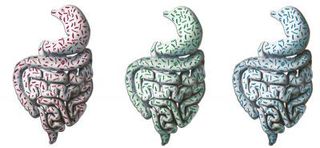

Similar to the classification of blood types, the bacteria in our guts appear to fit into one of three categories that have no relation to our nationality, age, sex and other characteristics, new research indicates.The study combined genetic information from about three dozen people in six countries, revealing that everyone falls into one of three categories they dub enterotypes, which they believe are spread around the globe just like blood types.

Humans' guts are home to swarms of bacteria. Members of this internal ecosystem help us with all sorts of important tasks, such as digesting food, assisting our immune systems and producing nutrients such as vitamin K. And research indicates there is a connection between these micro-organisms and some health problems, including obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. [Human Gut Loaded with More Bacteria than Thought]

Using an approach called metagenomics, researchers sequenced genetic material collected from fecal samples from 22 people in Denmark, France, Italy and Spain, and combined that with existing data from residents of Japan and the United States.

Their analysis revealed three enterotypes determined by the relative abundance of different networks of species, according to study researcher Peer Bork, a unit head at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Germany.

Overall, bacteria in the genus Bacteriodes — generally known for breaking down carbohydrates — were the most abundant overall, accounting for about 12 percent of all bacteria found in the samples, Bork said.

In fact, Bacteriodes dominated the first (and to a lesser degree, the third) enterotype. Another group, Prevotella, was quite abundant in the second enterotype. Ruminococcus was also an important contributor to the third enterotype.

The enterotype of a person did not appear to have any connection with their characteristics, such as gender, age, body mass index or nationality. There was, however, a caveat: Enterotype 1 appeared to make a stronger showing among Japanese individuals, though this may have been the result of the small sample size, which included data from only 13 Japanese people, according to Bork.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the type of bacteria present in the gut showed no connection to the host's characteristics, this was not the case for the bacteria's function. For instance, the presence of bacteria capable of breaking down starch appears to increase with someone's age. And men seem to carry more bacteria with the machinery to synthesize aspartate, an amino acid.

The findings, detailed in the most recent issue of the journal Nature, have implications for personalized medicine, in which treatments can be tailored to an individual's needs.

For example, "It's known that gut bacteria help in metabolizing drugs and change absorption behavior of human cells. It's likely that the three enterotypes do it in different ways, so optimal dosage of medicine (and balance of food) might be different for each enterotype," Bork wrote in an email to LiveScience.

Knowledge of enterotypes may also help with the development of techniques to restore healthy gut communities, rather than killing off all of the bugs living there with antibiotics, he wrote.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Most Popular