When Lung Cancer Resists Treatment, More Biopsies Needed

Why some lung cancers become resistant to targeted treatments has been somewhat of a mystery. Now a new study suggests more biopsies to understand how an individual patient’s cancer evolves may help to identify better therapies, researchers say.

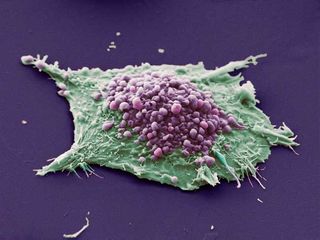

The study followed the course of 37 patients at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) with non-small cell lung cancer (the most common type of lung cancer), who were receiving drugs that targeted a mutated form of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in their tumors. In these patients, the treatments stopped working, and in most, a second biopsy had shown changes in the tumor to explain why this had occurred.

“Our study provides a broader, more in-depth perspective of the range of things you can find when these types of cancers become resistant to therapy,” said study investigator Dr. Lecia Sequist, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a medical oncologist at the Center for Thoracic Cancers at the MGH Cancer Center.

Sequist said that doing another biopsy to look at the tumors would result in a better course of treatment for patients after they stop responding to an initial treatment.

“The more you look, the more you find, and we’re making a lot of assumptions about a cancer just from one single snapshot in time,” she said.

The investigators found a number of changes that tumors had undergone to explain why targeted treatments were no longer working.

“The most surprising finding of our study was that a full 14 percent of the cases [five patients] actually switched from non-small cell lung cancer to small cell lung cancer,” said Sequist.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Small cell lung cancer is a faster-growing variety of lung cancer, and its rapid expansion is treated with chemotherapy, as surgical treatment is usually no longer an option.

The phenomenon of switching from non-small cell to small cell lung cancer had been noted in the past, but only documented in case studies and was thought to be rare. Doctors thought that it was the result of both non-small cell and small cell tumors growing at the same time. But Sequist said that was unlikely after looking at these cases, since the initial non-small cell and later small cell growths both had the same mutated EGFR, suggesting they were the same cells.

While that finding may have been the novel one, several other changes in the tumors accounted for treatment resistance.

In the most common change, occurring in about half of the cases, the EGFR simply mutates so that the drug no longer binds to it. This happened to 18 of the 37 patients in the study, sometimes along with another change to the tumor. Another common issue is that other parts of the tumor may simply mutate with growth elsewhere.

After a time off the EGFR-targetting treatment, some patients were able to resume it with success.

“The article raises some intriguing observations,” said Dr. Edward Kim, associate professor in the Department of Thoracic/Head and Neck Medical Oncology at MD Anderson Cancer Center, who was not involved in the current study. “The main message is biopsying patients is important to help us direct therapy.”

Kim told MyHealthNewsDaily that similar investigations are going on at MD Anderson as part of the BATTLE trials, where patients’ tumors are being looked at for biomarkers that may determine treatment options.

“The limitation we're always going to have when dealing with something like non-small cell lung cancer, we’re going to have to appreciate that the tumors can always be heterogeneous,” said Kim. “These changes can evolve over time, both dependent and independent of therapy. It’s hard to say if those were the result of the tumor responding to therapy or if those changes were just part of the evolving lung cancer process.”

He added that more tissue samples would enhance the ability to understand that evolution.

“Mandating biopsies is important so we can learn biology, not just only from treatment, but about the cancer itself,” said Kim.

Sequist agreed.

“Many patients have something when you look,” said Sequist, referring to various changes observed in their tumors. She noted that “there was still a percentage of patients where we didn’t find anything [to explain the resistance to treatment -- eight of the patients in the trial].”

But for patients where a reason for treatment resistance is found, “A lot of these things have drugs that are in clinical trials. If you find these types of mutations, there are trials that you as a patient may want to get on,” said Sequist. “These findings are not just useful for research — they are also useful for patients.”

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily on Twitter @MyHealth_MHND.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience.