Meltwater from Glaciers Could Warm Ice Even More

Meltwater flowing through cracks in glaciers and ice sheets could be the secret ingredient responsible for speeding up the warming of the massive blocks of ice and increasing their speed as they move, a new study suggests.

Thomas Phillips, a research scientist at the Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research, said scientists had thought meltwater moved through the ice fairly quickly before it reached the base and lubricated the bottom of the ice on its slow journey to the sea.

Upon closer examination, Phillips said, water apparently spends more time inside the ice than scientists realized.

Phillips developed a model that examines how this longer trickle-down time would affect the transfer of heat inside glaciers and ice sheets. His model predicts that water, flowing in subsurface rivulets and streams, even creating miniature lakes of standing water inside the glaciers, can be a significant warming agent.

"It doesn't take very much water to start warming up its surroundings," Phillips told OurAmazingPlanet. "Neglecting this has been one of the reasons why models haven't been able to reproduce what we're seeing."

What scientists have been seeing, said Thomas Neumann, a physical scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., is a lot of melting water. He used one of Earth's two ice sheets, the Greenland ice sheet, which is thousands of feet thick and host to many glaciers, as an example.

"As the climate warms in Greenland, you tend to get more surface melting," said Neumann, a specialist in the effects of temperature change on ice sheets. "We've seen over the last decade that the melt extent and melt volume in Greenland has been increasing."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Neumann said previous models hadn't been able to explain scientists' observations of the ice sheets and glaciers, and the new model introduces a possible mechanism to explain how changes in surface temperature can affect temperatures deep inside thick ice.

"The way we thought about it before was mostly through conduction – it's a relatively slow process," Neumann said.

He likened the conduction process inside glaciers to a process with which cooks are about to become reacquainted in kitchens across the country.

If you put a frozen turkey in the oven, Neumann explained, it takes quite a while for the center of the frozen bird to feel the effects of the heat. Phillips' model, Neumann told OurAmazingPlanet, is "a way to bring heat from the surface down into the ice much more quickly than just through conduction."

Phillips said one of the most important findings to come out of his recent work is that the meltwater's warming effect inside glaciers can rapidly increase the rate the bodies of ice are warming overall.

"A small change in temperature can really have quite a large impact in the increase of flow and speed," Phillips said, adding that changes would happen on the order of decades, instead of over millennia as previous models indicated.

Phillips emphasized that his findings so far are based on a model, and soon teams will set out for the Greenland ice sheet to take data to refine those findings.

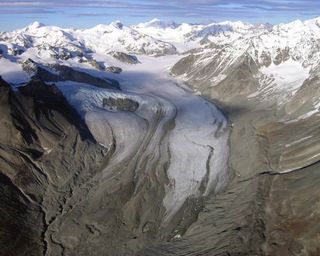

- In Images: Tracking a Retreating Glacier

- Glaciers May Have Soggier Bottoms Than Thought

- Image Gallery: Glaciers Before and After

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.