Electric Fish on Verge of Evolutionary Split

Electric fish emit weak signals from an organ in their tails that serves as a battery. Different emissions signal aggression, fear or courtship.

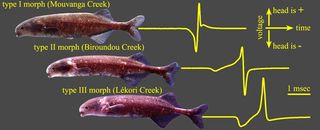

While the fish can apparently understand each others' warning signals, "They seem to only choose to mate with other fish having the same signature waveform as their own," explains neurobiologist Matt Arnegard of Cornell University.

But in the Ivindo River in Gabon, Arnegard and colleagues have found fish with the same DNA emitting distinctly different signals. The fish are likely on the verge of splitting into two species, the researchers announced today.

"We think we are seeing evolution in action," Arnegard said.

Electric animals

Because electricity is easily transmitted in water, many species of amphibians and fish have adapted to detect weak electric signals. Some, like sharks, use it to find prey. Others, like the electric eel, generate deadly voltages for defense or to kill prey. Others emit and detect electrical signals primarily as a means to communicate with their own kind.

Electric fish are called mormyrids. The roughly 20 distinct species that have been identified in the river, by their varying DNA, each emit distinct signals, which is the basis for Arnegard's new conclusion.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The process of splitting one species into two is called speciation. Scientists figure there are two ways it can happen. Groups can become geographically separated and take on new traits as their genes mutate. Or, animals can stay together but for some reason mate selectively to form distinct groups.

The latter method, called sympatric speciation, is seen to be less likely and somewhat controversial.

"Many scientists claim it's not feasible," Arnegard said. "But it could be a detection problem because speciation occurs over so many generations."

More work needed

Arnegard is a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Carl Hopkins, a Cornell professor who has been recording electric fish in Gabon since the 1970s.

The latest finding is detailed in the June issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Arnegard cautioned that it is possible the differing electrical signals might be like varying eye color and possibly won't result in speciation. He plans to return to the site this month to continue the research project, which is funded by the National Geographic Society.

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Most Popular